Weather

Wildlife banking on a warm spring

Today (1 March 2024) is the first day of meteorological spring. We cannot yet guarantee exactly what this spring will bring, but wildlife will be betting on another warm one, writes Grahame Madge – a Met Office climate spokesman and wildlife enthusiast – ahead of the United Nations’ World Wildlife Day on Sunday.

The red admiral butterfly can now be seen on virtually any warmish day in the UK. Previously it wasn’t an over-wintering species and it only used to occur here in the warmer months as a visitor from further south. Picture: Grahame Madge

For the UK, the five warmest springs since 1884 have all occurred since 2007. Wildlife is responding to this shift towards warmer springs by accelerating their own activities.

An index of spring – compiled from observations of the appearance of key spring wildlife species – is occurring many days earlier now when compared with the first half of last century.

The wildlife spring index shows the timing of biological spring events (the number of days after 31 December) in the UK. From 1891 to 1947 the Royal Meteorological Society provided the data, while from 1998 to 2022 it was provided by the UK Phenology Network (Nature’s Calendar, currently funded by the People’s Postcode Lottery, Postcode Green Trust). The Spring Index is calculated from the annual mean observation date of the following four biological events: first flowering of hawthorn; first flowering of horse chestnut; first recorded flight of an orange-tip butterfly; and first sighting of a swallow.

Already this year, at least one swallow has been reported in southern England; returning from Africa well ahead of the rest of its cohort. I have seen red admiral butterflies, bumble-bees and many chiffchaffs – a small usually summer-visiting songbird – in my corner of Exeter and sections of my walk to work have been lined with primroses. Anecdotally, these sightings are much earlier than I would expect.

However, my ad-hoc sightings in the margins of my dog-eared notebook are backed up by an army of wildlife fans diligently recording species across the UK through the Woodland Trust’s Nature’s Calendar scheme.

The recording of the timing of biological events is known as phenology. Two long-running nature surveys – monitoring four easily recorded species – have revealed that the average of time of appearance of these four species since 1998 is 8.7 days earlier than the average dates in the first part of the 20th Century. This is alarming, but not exceptional as other trends have been recorded too.

The dashed trend line in this graph shows that the UK spring has become more than 1.0°C warmer in the last 100 years.

A new course for the red admiral

The striking red admiral butterfly has always been a familiar visitor to parks and gardens the length and breadth of the UK. It used to be an exclusively migratory butterfly arriving on our shores after crossing the English Channel. But warmer winters are now altering this insect’s behaviour. Our winters are now becoming warm enough for it to overwinter as an adult to emerge on warm days in winter or early spring.

The warming of our climate is leading to a response from nature. The red admiral is an extremely abundant and seemingly adaptable insect, so it is unlikely to suffer any population consequences from this behaviour; at least at a species level. However, you have to wonder about the fate of those individuals encouraged to take their first flight of the year in winter, only to be hit by frost a few days later. What happens to them? My colleague Dr Mark McCarthy a Met Office climate statistics expert noted: “While frosts and cold spells in winter are falling, the date of first/last frost haven’t actually shifted all that much. So, although there are fewer frosts overall the risk of a ‘false spring’ in winter can increase the exposure to spring frosts later in the season. So, for parts of the environment and the agricultural and horticultural sectors there can be increased frost risks even with a declining trend.”

What happens when nature can’t rely on a warm spring?

Many species are making the most of warmer winters and springs to gain an ecological advantage and make the most of the changing seasons. In fact, they are banking on the UK’s climate statistics showing that winter and spring are becoming warmer, on average. But these trends are derived from seasonal averages of temperatures observed over a standard three-decade period. Occasionally, the actual temperature can be a long way from the long-term average and wildlife can be caught out by a colder-than-average spring. This happened in 2013.

The spring of 2013 was the coldest in the UK in 50 years. Some species were severely impacted. Although not a common event, springs as cold as 2013 happened more frequently in the late 19th and early to mid 20th Century.

The stone-curlew is one of England’s rarest birds, with a small and vulnerable population in southern and eastern England. Picture: Adobe Stock

In 2013 I worked for the RSPB, and we were being besieged by members of the public reporting odd birds turning up in gardens desperate for food and respite from the cold. The greatest concerns for a conservation organisation were the fates of those species whose populations had become severely depleted by other factors. The number one species of worry was for the stone-curlew, a species of wading bird thinly spread across parts of the agricultural landscapes of southern and eastern England. The birds spend the winter around the Mediterranean and arrive back on their nesting sites in early spring. Farmers were reporting numbers of these birds which had succumbed to the cold because of a lack of food. At the time the RSPB’s conservation director Martin Harper said: “I can’t remember a spring like this – nature has really been tested by a prolonged period of very cold weather.”

During parts of March 2013, the average temperature in the UK dipped to their lowest levels.

Climate change is affecting many species of wildlife. Some will adapt and others won’t. But even those with potential to adapt may be confounded by other factors, and populations which are already depleted will be less resilient to climate change impacts.

Weather

A wet and dull April

It will be no surprise for many to hear that April 2024 has been a wet month. In what has felt like an unsettled spring so far, the UK has had its sixth wettest April since the series began in 1836, according to provisional statistics from the Met Office.

Sunshine has been in short supply, with the UK provisionally recording just 79% of its long-term average for the month.

Wetter than average

The UK experienced 55% more rainfall than an average April, with 111.4mm falling across the month, making it the sixth wettest April in the series and the wettest April since 2012.

Many areas recorded more than their long-term average monthly rainfall, with Scotland experiencing its fourth wettest April in a series which started in 1836. It saw 148.9mm of rainfall across the month – more than 60% of its average and the wettest April since 1947.

Some places in Scotland saw more than double their average rainfall for the month. Edinburgh in particular saw very large rainfall totals, receiving 239% of its average April rainfall, which is its second wettest on record, falling only behind totals in 2000. East and West Lothian, Aberdeen, Clackmannan, Berwickshire and Cumbria, among others, also recorded more than double their average rainfall in the month. A rain-gauge at Honister Pass in the English Lake District recorded more than 400mm of rain.

Met Office Scientist Emily Carlisle said: “April has been a continuation of the past few months: often wet, windy and unsettled. April showers were present from the beginning of the month, with frontal systems bringing persistent precipitation across the UK. Although a high-pressure system moved over the UK on the 20th bringing some drier weather, by the end of the month, low pressure was back in charge, bringing with it more rain.”

Temperatures around average

April was a month of two halves when it comes to temperatures. The month started off warm, particularly along the southeast coast of England. Writtle in Essex recorded 21.8°C, making it the hottest day of 2024 so far in the UK.

Temperatures then dropped, remaining slightly below average for most of the last two weeks of April. This balanced out the warmer temperatures at the start of the month and resulted in a provisional average mean temperature of 8.3°C for the UK, only 0.4°C higher above the 1991-2020 long-term average.

Cloudy conditions often resulted in overnight temperatures being held up, with the average minimum temperature being above average (+0.8°C).

A dull month

Along with being a wet month, April has also been a dull month. The UK provisionally recorded 79% of the long-term average sunshine duration, with 122.9 hours.

One named storm

April saw Storm Kathleen arrive on the 6th, bringing heavy rain to Scotland, Wales, parts of Northern Ireland and the west coast of England. Kathleen also brought strong winds across the UK, with gales along coasts, particularly in the north and west of the UK. Kathleen was the eleventh named storm of the 2023/24 season. This is only the second time that the Met Office has reached the letter K since they began naming storms in 2015.

Spring so far…

Meteorological spring (March to May) so far has been wet. Both England and Wales have already seen more than their long-term average rainfall for the entirety of the season, while the UK has seen 96%. At this point in the season, we’d expect to see 66% of average.

| Provisional April 2024 | Mean temp (°C) | Sunshine (hours) | Rainfall (mm) | |||

| Actual | Diff from avg (°C) | Actual | % of avg | Actual | % of avg | |

| UK | 8.3 | 0.4 | 122.9 | 79 | 111.4 | 155 |

| England | 9.3 | 0.6 | 127.0 | 78 | 85.5 | 152 |

| Wales | 8.5 | 0.4 | 113.3 | 72 | 135.8 | 154 |

| Scotland | 6.6 | 0.0 | 119.2 | 84 | 148.9 | 160 |

| N Ireland | 8.3 | 0.3 | 118.4 | 80 | 104.6 | 141 |

Weather

Antarctic sea ice in 2023

Each year, from June-October, polar climate scientists from the Met Office produce a series of monthly sea ice briefings for the government and the general public. These briefings describe the state of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice, compare how these relate to historic patterns, and, where possible, assess causes of unusual behaviour.

Sea ice is frozen seawater that floats on the surface of the ocean and is found when temperatures are cold enough for sea water to freeze. The extent of sea ice is a key climate indicator, because sea ice cover insulates the ocean in winter and reflects sunlight in summer, as well as providing a habitat for a range of species.

Here, Senior Scientist Alex West talks about the 2023 Antarctic sea ice minimum and its interaction with the ocean and atmosphere.

Lowest sea ice extent on record

Antarctic average sea ice extent for 2023 was the lowest on record. During the ice growth season from June-October, ice extent was exceptionally low for the time of year, reaching over 1 million square km below previous record lows and setting a new record low maximum extent by a very large margin. For much of the rest of the year, the ice was at record or near-record low levels, recording a second successive record low minimum in February (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Antarctic sea ice extent in 2023 (bold black line) with other recent years indicated, as well as earlier years with notably low sea ice extent. The 1981-2010 average is also shown, with the shaded region indicating 2 standard deviation intervals.

The very low extent from June-October was partly caused by enhanced warm northerly winds, associated with persistent areas of high and low pressure (Ionita, 2024). Early in the ice growth season, from May-July, these were concentrated near the Antarctic Peninsula, in the Weddell and Bellingshausen Sea regions; later in the growth season, from August-October, the strongest winds were to be found further west, in the Ross Sea. The position of the lowest sea ice conditions changed similarly.

However, it is likely that the ocean also played a part. The low extent of 2023 continues a pattern of very high variability in Antarctic sea ice since 2007, with first high and then low sea ice conditions persisting for long periods of time, in a way unlikely to be caused by known atmospheric changes (Hobbs et al., 2024). A key moment in this period of high variability was a large reduction that occurred in 2016, and this is thought to be linked to changes in the upper ocean caused by stronger westerly winds mixing warmer waters below towards the surface (Earys et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Further mixing of warm waters cannot be ruled out as an additional cause of the very low extent of 2023.

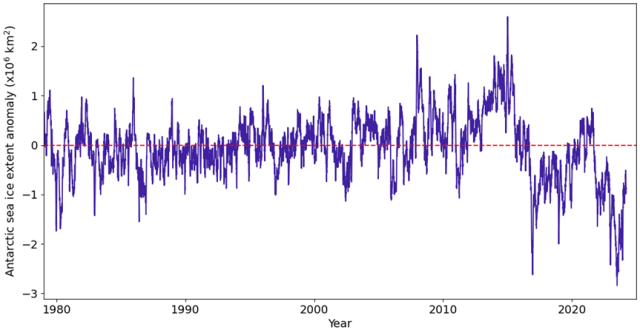

The precise contribution of anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming to the record low sea ice of 2023 is not yet known. While climate models predict that Antarctic sea ice extent will decrease in response to anthropogenic warming, variability in the past 15 years has been considerable, with very high extent from 2012-2014 followed by the current period of very low extent (Figure 2). Further extreme variability in either direction remains possible in the years ahead.

Figure 2. Antarctic sea ice monthly anomalies over the period of satellite observations. For each month, the 1981-2010 average ice extent for that month is subtracted. This largely removes the seasonal cycle so that subtler long-term changes can be viewed more easily.

During April we are exploring the topic of the ocean and climate. Follow the #GetClimateReady hashtag on X (formerly Twitter) to learn more throughout the month.

References

Eayrs, C., X. Li, M.N. Raphael and D.M. Holland (2021) Rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice in recent years hints at future change. Nat. Geosci., 14, 460–464. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00768-3

Hobbs, W., and Coauthors (2024): Observational Evidence for a Regime Shift in Summer Antarctic Sea Ice. J. Climate, 37, 2263–2275, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-23-0479.1

Ionita M (2024) Large-scale drivers of the exceptionally low winter Antarctic sea ice extent in 2023. Front. Earth Sci. 12:1333706, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2024.1333706

Zhang, L., T.L. Delworth, X. Yang, F. Zeng, F. Lu, Y. Morioka and M. Bushuk (2022) The relative role of the subsurface Southern Ocean in driving negative Antarctic Sea ice extent anomalies in 2016–2021. Commun. Earth Environ., 3, 302. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00624-1

Weather

NEMO: a numerical ocean model

A numerical ocean model is a computer programme representing the equations of motion (momentum, conservation of mass and thermodynamics) for the ocean. The model stores each of the physical properties of the ocean (temperatures, salinities and currents) on a three-dimensional grid, writes Ana Aguiar.

Smaller ocean features can be resolved by using a finer grid with more points, but this requires more computational power. The model evolves these physical properties forward in time using its equations of motion. Models of sea ice and biogeochemistry work using similar principles.

Why do we need a numerical ocean model?

We need these models to predict the state of the ocean within short and long timescales for a variety of purposes, ranging from support to operations at sea (for example, search and rescue) to understanding the role of the ocean in the Earth’s climate system. As the ocean sits beneath the atmosphere, sea-surface temperature patterns have widespread impact on the weather over land. Largely because two-thirds of the Earth is covered by ocean and the heat capacity of water considerably outweighs that of the air, the ocean acts as a regulator of the atmosphere.

In polar regions temperatures become cold enough for seawater to freeze and sea ice forms on the surface of the ocean. Sea ice plays an important role in the climate system because it insulates the ocean from the colder atmosphere in winter and, being whiter than the ocean, reflects sunlight in the summer.

The NEMO modelling framework includes a sea-ice model component, known as SI³ (Sea Ice modelling Integrated Initiative). The sea-ice component is run along with the ocean component in a similar manner but using a different set of equations. To understand and prepare for climate change we need to account for the role of the ocean and sea ice.

How is the NEMO model developed?

Nucleus for European Modelling of the Ocean (NEMO) is a state-of-the-art ocean modelling framework. NEMO is developed by a European consortium with the objective of ensuring long-term reliability and sustainability of the code. In other words, the task of maintaining and developing such a complex computer programme requires a well-coordinated team effort, involves tens of developers and hundreds of users.

In the UK there are two member organisations: the Met Office and the National Oceanography Centre (NOC). Met Office Scientific Manager in Ocean Modelling, Ana Aguiar explains: “We work in partnership through the Joint Marine Modelling Programme, contributing to the development of NEMO. The code is publicly available for use in research and commercial applications. It is imperative to reach as many users as possible, to ensure the code gets tested and pushed to the limits of its usability. User requirements then prompt further advances.”

NEMO benefits from continual work to improve its performance (scientific and computational efficiency), to incorporate new scientific and process understanding, and to exploit the increase in supercomputer resources. When the developments are sufficiently mature and can provide significant scientific or technical improvements, a new NEMO version is released. Along with scientific upgrades (which tend to be increasingly computationally demanding), we must deliver code optimisation to make the best use of the available computing resources.

This video presents how NEMO is used by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service.

What’s next?

The next NEMO release (expected to be rolled out this summer) will deliver significant improvements to model performance allowing it to run considerably faster. In the long term, among other things, we are also working towards porting the NEMO code to Graphical Processing Units (GPUs) to ensure continuity of the code in future mainstream High Performance Computing architectures

During April we are exploring the topic of the ocean and climate. Follow the #GetClimateReady hashtag on X (formerly Twitter) to learn more throughout the month.

-

African History3 months ago

African History3 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History4 years ago

African History4 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History2 years ago

African History2 years agoHow Did Normal Medieval People Survive Winter? | Tudor Monastery Farm | Chronicle

-

African History3 years ago

African History3 years agoThe Entire History of Africa in Under 10 Minutes – Documentary

-

African History3 years ago

African History3 years agoWhat happened to the many African Kingdoms? History of Africa 1500-1800 Documentary 1/6

-

African History2 years ago

African History2 years agoAFRO MEXICO: Black History In Mexico!

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoA Black African King in Medieval European Art