Sci-Tech

The Future of Netflix, Amazon and Other Streaming Services

When the media titans Brian Roberts, John Malone and Barry Diller cast off in early February on Mr. Diller’s 156-foot, two-masted yacht, named Arriva, the waters off the coast of Jupiter, Fla., were placid.

The same could not be said for their sprawling entertainment businesses.

The three men meet occasionally to discuss the state of the industry, and lively disagreements have a been a staple of their discussions. But by the time they met on the yacht, they had all agreed that the money-losing status quo in the streaming business was unsustainable. The old cable model was a melting ice cube.

But what will take its place?

“There was peace in the valley for a period of time,” Mr. Malone mused in a rare recent interview, recalling the days before video-streaming upended the lucrative cable business. “Now, it’s quite chaotic.”

That is likely an understatement: The once-mighty Paramount, which owns the famed Paramount studio, CBS and a bevy of cable channels, recently replaced its chief executive and failed to sell itself after months of negotiations. Warner Bros. Discovery is frantically paying down its $43 billion in debt. Disney laid off thousands of workers and pushed out its chief executive as streaming losses mounted, and had to fend off a proxy contest from the activist investor Nelson Peltz.

The stocks of legacy media companies are a fraction of their former highs: Paramount is near $10 a share and Warner Bros. Discovery is hovering around $7, both down drastically from levels reached during the past year. Even Disney, at about $102, is down more than 16 percent from the price reached in March.

No wonder: Paramount, the media empire controlled by Shari Redstone, lost $1.6 billion on streaming last year. Comcast lost $2.7 billion on its Peacock streaming service. Disney lost about $2.6 billion on its services, which include Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+. Warner Bros. Discovery says its Max streaming service eked out a profit last year, but only by including HBO sales through cable distributors.

At the same time, shares of the disrupters — Netflix and Amazon — are close to record highs.

Mr. Malone, Mr. Roberts, and Mr. Diller all came of age during the golden era of television. Mr. Malone, 83, clawed his way to a multibillion dollar fortune by building a cable empire, and is an influential shareholder in Warner Bros. Discovery and a longtime mentor to its chief executive, David Zaslav. Mr. Roberts, 64, succeeded his father as chairman, chief executive and the most influential shareholder of Comcast. Since then, he has transformed Comcast into a broadband giant and, by acquiring NBCUniversal, into a media powerhouse. Mr. Diller, 82, is chairman of IAC, the digital media company, and a veteran TV and movie executive. His long and successful tenure in entertainment and media has earned him a position as one of the industry’s most sought-after senior statesman.

By comparison, the heads of the disrupters, Netflix and Amazon, are younger, brash newcomers, with little attachment to Hollywood’s golden age.

Ted Sarandos, 59, co-chief executive of Netflix, worked his way up through the now-defunct DVD industry before going straight to Netflix when the company was still renting DVDs by mail. Mike Hopkins, 55, head of Prime Video and Amazon MGM Studios, was steeped in digital as chief executive of Hulu, the pioneering streaming service owned by Disney, Fox and NBCU, before joining Sony as head of its television unit in 2017. He came to Amazon in 2020 and reports to the company’s chief executive, Andy Jassy, 56, who has no professional background in entertainment.

Over the past five months, The New York Times interviewed those three older executives, and the two younger ones, as well as numerous other owners and senior executives of major media companies to assess the problems facing the industry and what the future landscape could look like.

Rarely do these executives speak so candidly, on the record, about the challenge in front of them. And the meetings on the yacht aside, rarely do executives in that stratosphere get together to discuss strategy. Not only are many of them fierce rivals — Mr. Roberts famously drove up the cost of Disney’s 2019 acquisition of 21st Century Fox’s entertainment assets by bidding against Disney’s chief executive, Bob Iger — but meetings among direct competitors might attract unwelcome attention from antitrust regulators.

In our conversations, there were still plenty of disagreements, but some consistent themes emerged as well — all with major implications for investors, advertisers and audiences.

The Magic Subscriber Number

Streaming has long been hailed as a promising business, because companies like Netflix can add additional subscribers at little extra cost. The more paying subscribers a service has, the more the company’s costs can be spread out over a large base, lowering the cost per subscriber.

But those subscribers want lots of options, and the costs of making enough programming can be enormous. As a result, a streaming service’s profitability depends in large part on how many paying subscribers are needed before those TV shows and movies become cost-effective.

There was a time when industry executives hoped that number might be as low as 100 million.

But now the consensus among many of the executives interviewed is that the number is at least 200 million, and possibly more.

“If you’re going to be a full entertainment service with live sports and tent-pole blockbusters today, 200 million is a number that can give you the scale with the hope for growth over time,” Mr. Hopkins of Amazon said.

Bob Chapek, Disney’s chief executive until 2022, also agreed that 200 million was the number that meant “you’re big enough to compete.”

Netflix has reached that, and then some, with about 270 million paying subscribers. Moreover, those subscribers pay an industry-leading average of more than $11 per month.

Netflix is highly profitable, with operating margins of 28 percent. In the first quarter of 2024, Netflix reported revenue of $9.4 billion, and $2.3 billion in net income. No one else comes close.

Disney and Amazon are the only other streaming services with more than 200 million subscribers. While Amazon doesn’t disclose the number of its Prime Video subscribers, Mr. Hopkins said the number was well above 200 million and growing. Disney+ and Hulu, which is also owned by Disney, have just over 200 million subscribers combined.

In May, Disney said its entertainment streaming services eked out a small profit. Amazon doesn’t disclose profit margins or losses, and streaming is embedded in a package of Prime services. But Amazon’s chief executive, Andy Jassy, has said that Prime Video will be “a large and profitable business” on its own.

$50 Million an Episode, Over and Over

The costs of attracting — and keeping — those millions of customers is no cheap feat.

Overall, Netflix has said it will spend about $17 billion this year on programming, about what it did before last year’s Hollywood strikes depressed production. That level of spending has produced a golden age for A-list writers and actors, many of whom are flocking to the company. A new series, “3 Body Problem,” debuted a few months ago on Netflix at a reported cost of about $20 million per episode. It spent more than $200 million on “The Gray Man,” starring Ryan Gosling.

“It’s a tall order to entertain the world,” Mr. Sarandos of Netflix said. “You have to do it with regularity and dependably.”

For Netflix, $17 billion represents only about half of its total revenue. But almost no competitor can match that spending level, the executives said, except for maybe Amazon. Amazon spent $300 million for six episodes of the spy thriller “Citadel,” or $50 million per episode — one of several major bets it has made.

Not all of those pay off. But when they do, the impact can be huge, like wildcatters when they hit a gusher. Amazon paid $153 million for one season of “Fallout,” a series based on the popular post apocalyptic video game. In April, “Fallout” was the top streaming title, racking up over seven billion viewing minutes, according to Amazon.

Mr. Sarandos held out the company’s recent “Baby Reindeer” series as a prime example of why companies have to keep spending: because viewers expect a nearly endless supply of options, or they will hit the unsubscribe button.

“When you finish ‘Baby Reindeer,’ there’s something else just as good,” he said. “I worry that this notion of these other services, that they have nothing to watch problem, and that once you do a show and then you drag it out over 10 weeks or doing one episode at a time, you still end up in the same place, which is there’s nothing to watch after it.”

The data appear to bear him out. When cable TV was in its heyday, 1.5 to 2 percent of subscribers churned monthly, abandoning or suspending their service. The average churn across all streaming services is more than double that, according to data from analytics firm Antenna, with the churn rate of some smaller streaming services, like Paramount+, as high as 7 percent. Only Netflix has a churn rate below 4 percent.

Some executives who oversee rivals to Netflix and Amazon say their companies can reduce spending by only producing hits. But that’s been the holy grail ever since Hollywood was created, and no one has succeeded over the long term. Even Disney’s Marvel franchise has stumbled at the box office lately.

That means streaming services need the resources to invest in a wide variety of projects, knowing there will be some, even many, relative failures for every hit. (“Citadel” is a case in point — it never made Nielsen’s top 10 streaming shows.)

“It’s still more art than science,” Mr. Sarandos said.

Play Ball

Adding to the cost pressure, the executives said, is the soaring cost of sports programming. Even in the bygone era of traditional television, the broad appeal of sports was obvious. The big networks paid billions for must-see events like the Super Bowl and the N.B.A. Finals and much of what was left over went to Disney and Hearst-owned ESPN, one of the most lucrative cable franchises ever created.

But that was before streaming and the arrival of the deep-pocketed tech giants. Amazon now offers football games from the National Football League, NASCAR races, the W.N.B.A. with its newly minted star Caitlin Clark, the National Hockey League in Canada and Champions League soccer in Germany, Italy and Britain.

Apple TV+ also features Major League Baseball, as well as Major League Soccer.

Alphabet’s YouTube offers N.F.L. Sunday Ticket, a lineup of out-of-market football games. Even Netflix, which long shunned live sports, announced in May that it would stream N.F.L. games on Christmas Day for the next three years.

The appeal of live sports is both unique and twofold: They attract new streaming subscribers and reduce churn since viewers want to watch sports live. It is also a big draw for advertisers as streaming services look to grow their ad businesses.

It may not be an overstatement, the executives said, to say that a streaming service can’t survive as a stand-alone business without sports.

Comcast’s Peacock scored a huge success in January with its exclusive N.F.L. playoff game between Kansas City and Miami. The game was the biggest livestreaming event ever, with about 32 million viewers. (Comcast’s NBC network pays $2 billion annually for a package of N.F.L. broadcast rights.)

“Sports seems like the simplest and most interesting thing,” Mr. Malone said.

The result is bidding wars unlike anything experienced before in the media industry, currently on display during the protracted negotiations for a new 10-year N.B.A. rights contract. The rights, which are now shared by ESPN and Warner Bros. Discovery’s Turner cable network, are being chased by NBC and Amazon, as well as ESPN and Warner Bros. Discovery.

While ESPN, Amazon and NBC are finalizing deals for their packages, Warner Bros. Discovery is seen at risk of being outbid, though executives at Warner Bros. believe they have the legal rights to match Amazon’s bid. Many in the industry expect that the final deal will be more than triple the last N.B.A. contract.Which raises questions that executives didn’t have a clear answers to:

As the cost of rights soars, will the streaming services actually make money on them? Or will marquee sports events function as loss leaders, drawing viewers to other fare, as they once did for the old broadcast networks?

Advertising to the Rescue?

Wall Street analysts and investors in streaming once fixated entirely on the number of subscribers, ignoring losses, in the belief that prices would someday rise substantially. That changed with dizzying speed in early 2022, when Netflix announced it had lost subscribers for the first time in a decade.

It’s now clear that price increases won’t be the answer to streaming profitability for most services, the executives said. Netflix is the industry price leader and has pushed its monthly fee in the United States to $15.49 a month without ads. Few believe the monthly fee can get much above $20 a month for the foreseeable future.

After years of championing an ad-free consumer experience, Netflix introduced an ad-supported subscription in 2022 at a steep discount of $6.99 a month. Disney+, Hulu, Amazon, Warner Bros. Discovery’s Max, Peacock and Paramount+ all offer cheaper, ad-supported subscriptions.

“It’s a nice way to get price-sensitive consumers,” said Mr. Chapek, who introduced an ad-supported tier while running Disney. “Heavy users will still come and pay the higher monthly fee.”

Mr. Chapek acknowledged that advertisers covet — and will pay more for — mass audiences. As a result, the streaming services have a strong incentive to produce programs with broad appeal instead of more niche content, including some of the kind that generates critical acclaim.

Netflix shocked many in the industry last year when for the first time it revealed its most-watched programs over the prior six months. At the top were “The Night Agent,” an action-thriller, and “Ginny and Georgia,” a comedy-drama about a mother and daughter trying to forge a new life. Both shows were snubbed by Emmy voters, with a lone nomination for a song from “Ginny and Georgia.” (“Squid Game,” developed in Korea, is Netflix’s most-watched program ever.)

Advertisers, the executives say, also like that streaming services can target ads to specific users and demographics.

The results have been explosive. Netflix is on pace to generate roughly $1 billion in advertising revenue this year, according to estimates from eMarketer, and Disney has already generated $1.7 billion this fiscal year.

That kind of success suggests that streaming ads are here to stay. And some of the executives said streaming services predicted that companies would raise prices aggressively on ad-free tiers in an effort to drive consumers to ad-supported versions.

Who Will Survive?

How many streaming services will consumers support? That was one of the great mysteries of the nascent streaming world, and the answer is coming into focus: not very many.

“Can your current business be a successful player and have long-term wealth generation, or are you going to be roadkill?” Mr. Malone mused. “I think all the small players will have to shrink down or go away.”

A recent Deloitte study found that American households paid an average of $61 a month for four streaming services, but that many didn’t think the expense was worth it.

That suggests the once-unthinkable possibility, many of the executives said, that there will be only three or four streaming survivors: Netflix and Amazon, almost certainly. Probably some combination of Disney and Hulu. Apple remains a niche participant, but appears to be feeling its way into a long-term, albeit money-losing, presence, which it can afford to do. That leaves big question marks over Peacock, Warner Bros. Discovery’s Max, and Paramount+.

Peacock, with just 34 million subscribers, isn’t trying to be another Netflix. By focusing on North America, and not trying to be all things to all customers, Mr. Roberts believes Peacock can achieve success on its own terms.

Peacock also has the advantage to being embedded in the much larger Comcast, with its steady cash flow.

“We all have a different calculus to define success in streaming,” Mr. Roberts said. “As online viewing increases and internet usage skyrockets, I believe we have a special set of assets that put us in position to continue to monetize and more importantly innovate as this transition happens.”

The Bundling Conundrum

After years of go-it-alone strategies, “bundling” — offering consumers a package of streaming services for a single fee — has become the latest strategy for reaching profitability among the smaller services.

In May, Comcast announced it would offer its broadband customers a bundle of Peacock, Netflix and Apple TV+ for $15 a month. Disney has bundled Disney+ and Hulu, with Max to be added this summer at an as-yet undisclosed price. Venu, a new sports streaming joint venture from Disney, Fox and Warner Bros. Discovery, is planning its release this fall.

However innovative the arrangements, the executives said, the economics of bundling are complicated. Participants need to attract consumers who wouldn’t already subscribe to their individual channels at full price. They must also puzzle through how revenue should be divided among bundling participants of unequal stature.

It’s also unclear that bundling will achieve the scale that participants may be hoping for. Many customers already subscribe to one or more of the bundle options. So it’s not a matter of simply adding up subscribers. And if multiple subscriptions are offered at a discount to attract customers, the average revenue per user declines.

Jason Kilar, the founding Hulu chief executive and former chief executive of WarnerMedia, has called for an even more radical approach than bundling: a new company that would license movies and TV shows from the major studios and pay back close to 70 percent of the revenue to those studios.

“I’ll call it the ‘Spotify for Hollywood’ path, where a large number of suppliers and studios contribute to a singular experience that delights fans,” Mr. Kilar said. “The studios would be the ones that would be taking the majority of the economic returns from such a structure.”

Media companies have started to embrace licensing deals after a period of avoiding them. During AT&T’s ill-fated ownership of WarnerMedia, the company insisted that its content be shown exclusively on its Max streaming service. Disney pulled back on licensing deals when it started Disney+ in an effort to force fans to subscribe. Before he returned to Disney, in 2022, Mr. Iger compared licensing the company’s franchises to selling nuclear weapons to “third-world countries.”

But AT&T subsequently abandoned streaming, merging WarnerMedia into Discovery, and Mr. Iger has since embraced the nuclear option. Both Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery are again licensing their content to rivals Netflix and Amazon Prime.

Sony Goes Another Way

One company embodies the embrace of the licensing strategy: Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Sony, the studio behind “Spider Man” and “Men in Black,” rejected general entertainment streaming services years ago. Tony Vinciquerra, the company’s chief executive, instead adopted what he has called an “arms dealer” strategy, selling movies and TV shows to companies like Disney and Netflix.

The exception is that Sony operates a niche streamer, Crunchyroll, that focuses on anime, Japanese-style hand-dawn animation. Its success suggests that a small (more than 14 million subscribers worldwide) and low-cost operation can be profitable without going up against Netflix.

Mr. Vinciquerra pointed out that Sony’s rivals running big streaming businesses were losing money on those services while at the same time seeing their traditional cable networks in decline.

“I’m still scratching my head wondering what these companies will do here,” Mr. Vinciquerra said, referring to the declining cable networks. “They all have these massive albatrosses around their neck that they can’t do anything about right now.”

So far, Sony’s strategy appears to be working. Sony’s Pictures Entertainment generated almost $11 billion of revenue in 2023, a 2 percent increase from the same period a year earlier, according to filings. In 2021, Sony struck deals to license movies to both Netflix and Disney worth an estimated $3 billion annually. Profits were roughly $1.2 billion, 10 percent lower than the previous year because of the actors’ and writers’ strikes.

Unlike Paramount or Disney, Sony Pictures is part of a sprawling global consumer electronics conglomerate. Sony recently teamed up with the private-equity giant Apollo Global Management to make a $26 billion bid for Paramount. But Sony is interested only in Paramount’s film library and characters like SpongeBob SquarePants and has contemplated selling the rest of it — including the Paramount+ streaming service. But Sony has since backed away from its offer.

That’s just the latest indication that expectations for merger deals have faded. Paramount is still looking for a buyer after months of tortured negotiations and is revamping its streaming strategy in the meantime. So far as is known, no one is pursuing Warner Bros. Discovery, free since April, to buy or be sold under the terms of its separation from AT&T. Potential buyers like Comcast are understandably wary of their decaying revenue bases in cable. And Disney is shackled with its own cable issues and is loaded with debt from buying 21st Century Fox.

The End of a Golden Age

All of these changes have had a big upside for viewers.

“It’s been a golden age, even with prices rising,” Mr. Chapek said. “You get entire libraries built over decades plus all this new content, and you watch at your leisure.”

But a change is underway, he said: “Now we just have to make it viable for shareholders.”

That will necessarily mean higher prices for customers, more advertising, and less — and less expensive — content. That’s already happening. On average, consumers spend 41 percent more on streaming than they did a year ago, according to the recent Deloitte study, while satisfaction has declined. While some of that may be because of the limited new content offered last year during the Hollywood strikes, Disney and pretty much everyone except Netflix and Amazon have vowed to reduce spending and produce less new content.

The rise of advertising may be a windfall for streaming services, but the quest for the mass audiences that advertisers seek risks turning the streaming landscape into a sea of police procedurals and hospital dramas punctuated by major sports events and blockbuster concerts. Ironically, that’s pretty much the old model once dominated by the four ad-supported broadcast networks.

Netflix and Amazon executives acknowledge the risks to high-quality programming but promise that won’t happen on their watch. They contend they have enough scale that their prestige programs can be profitable and reach a vast audience — even if it’s a small percentage of their overall subscriber base.

“We can do prestige TV at scale,” Mr. Sarandos said. “But we don’t only do prestige,” he added, citing popular shows like “Night Agent.”

Mr. Hopkins of Amazon said “procedurals and other tried and true formats do well for us, but we also need big swings that have customers saying ‘Wow, I can’t believe that just happened’ and will have people telling their friends.”

“We want rabid fans,” he said.

Bryan Lourd, chief executive and co-chairman of the powerful Creative Artists Agency, said media executives needed to put aside financial engineering and remember that creativity — and entertaining customers — was the only way to win in the long run.

“The task at hand is to keep the customer at the front of your brain,” Mr. Lourd said. “When people stop doing that is when things start to go wrong.”

And Yet, Continued Optimism

On Mr. Diller’s yacht that day in February, Mr. Malone’s advice to Mr. Roberts was simple: In light of the challenges facing the industry, Comcast should continue its current strategy of investing in other areas like theme parks.

“Now, are they large enough to be the biggest?” said Mr. Diller, speaking generally about streaming services besides Netflix. “No, that game was lost some years ago. Netflix commands not all the territory, but they command the leading territory right now. They essentially are in a position of dictating policy.”

But Mr. Diller, like many of the other executives interviewed for this article, see a path forward for streaming companies once they stop trying to be Netflix. (That’s the strategy already adopted by Mr. Roberts of Comcast.)

The focus, according to Mr. Diller, needs to be on what “has been true since the beginning of time.”

The business, he said, “is based on hit programming, making a program, a movie, a something that people want to see.”

Sci-Tech

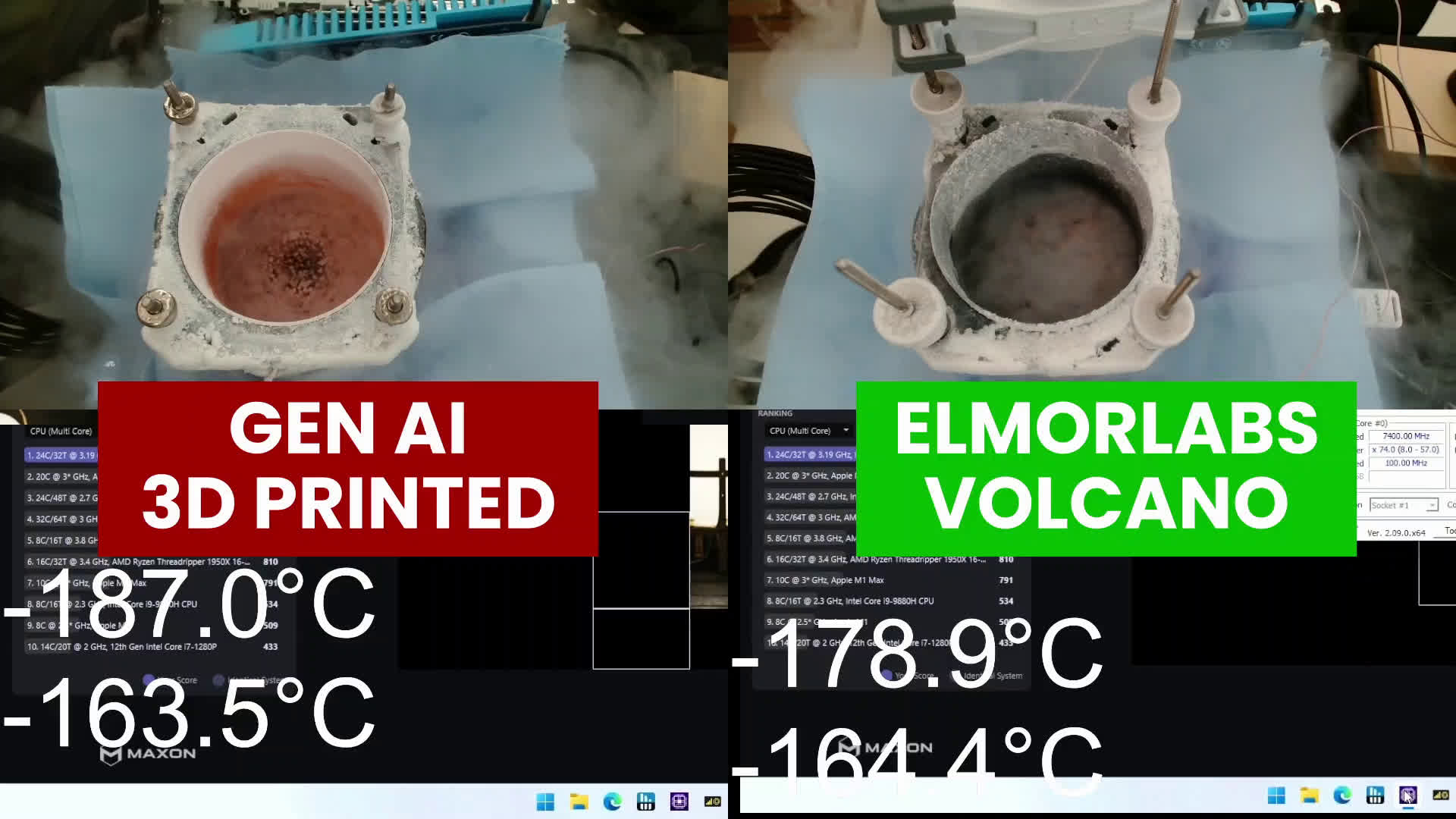

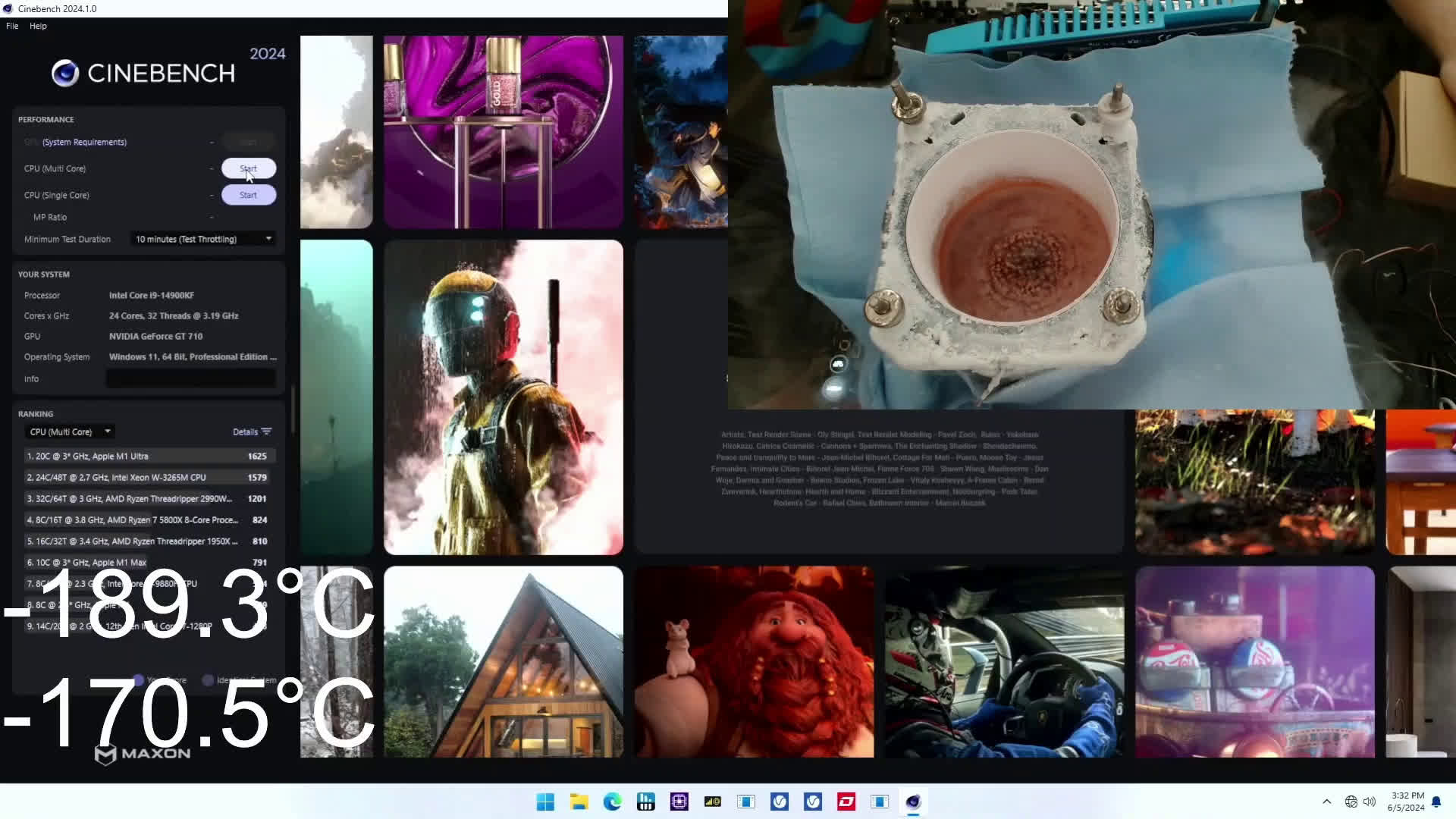

$10,000 cooler designed with AI keeps Core i9-14900KF chilly at 7.5 GHz

Pushing the limits: Enthusiasts are always looking for an edge in the world of overclocking and extreme cooling. In this wild test, the team sought to determine whether advanced GenAI and 3D printing could help them squeeze out more performance from today’s processors. To answer this, they built a liquid nitrogen (LN2) container in a whole new way – and arrived at some interesting conclusions.

The project brought together experts from across the ecosystem – Skatterbencher who’s renowned for overclocking prowess; Diabatix, specializing in generative AI for thermal solutions; 3D Systems for additive manufacturing; and finally ElmorLabs for overclocking gear.

The team took ElmorLabs’ existing Volcano LN2 container as a reference point, then tasked Diabatix’s ColdStream Next AI to generate an improved design. 3D Systems then brought that digital blueprint to life, 3D printing a prototype using oxygen-free copper powder. Shockingly though, the cutting-edge process commanded a steep $10,000 price tag – a far cry from the $260 cost of the original Volcano.

The AI/3D printed design showed promise in early testing, focusing on three key metrics: cool-down time from room temperature to -194°C, heat-up time from -194°C to 20°C under a 1250W load, and the lowest temperature achieved using 500mL of liquid nitrogen.

It blew past the Volcano in cool-down speed, chilling from 28°C to -194°C in under a minute compared to the Volcano’s 3-minute pace. Heat-up performance was better too, with the AI container warming up 30% faster. Efficiency also favored the AI design – using 500mL of LN2, it hit -133°C, while the Volcano stopped short at -100°C.

However, since these tests do not represent real-world performance, the team decided to run three more using the Intel Core i9-14900KF Raptor Lake processor. First, they fired up Cinebench 2024 to find the most stable maximum CPU frequency.

“We find that both LN2 containers can handle the Core i9-14900KF with P-cores clocked to 7.4 GHz without any issue. It seemed the AI-generated design could perhaps hold 7.5 GHz just a tad longer. But that might just be run-to-run variation,” they noted.

In the second test, they checked the CPU temperature deltas between the heat spreader and cooling container base to assess real heat transfer capabilities. There was also an all-out stress test, pushing over 600W through the chip for several minutes.

While the AI container did pull ahead a smidge, the gains were relatively muted compared to the theoretical test results. Temperature deltas between the CPU heat spreader and container base were tighter on the 3D-printed model, but not by an earth-shattering margin. Even the performance uplift in Cinebench was fairly modest, as seen above.

After crunching the numbers, the team determined that while technically impressive, the AI/3D printed design currently doesn’t pencil out from a cost/benefit perspective for modest overclocking scenarios. Not with that $10,000 price tag.

However, they are not done yet. While “nothing concrete” is in hand, the team says they could look into performance and cost optimizations. The design of the LN2 container doesn’t necessarily need to be circular, for example. They are also exploring new designs for higher-power CPUs like the Ryzen Threadripper or Intel’s Xeon 6.

All in all, the feasibility study may have exposed some limitations, but it also proved generative AI has better uses than simply churning out six-fingered models.

Sci-Tech

Microsoft resumes rollout of Windows 11 KB5039302 update for most users

Microsoft has resumed the rollout of the June Windows 11 KB5039302 update, now blocking the update only for those using virtualization software.

On Wednesday, Microsoft pulled the KB5039302 update after Windows 11 users found that their devices went into a reboot loop after it was installed.

After investigating the issue, Microsoft determined that the bug mostly affects devices that utilize virtual machine tools and nested virtualization features, such as CloudPC, DevBox, and Azure Virtual Desktop. Others stated it also affected VMware.

Yesterday, in an update to Windows Message Center, Microsoft once again resumed rolling out the KB5039302 update to those not running virtualization software.

“Availability of this update via Windows Update and Windows Update for Business was paused for a couple of days, but is being resumed today for most devices,” reads the message center update.

“This update offering is now paused only for devices affected by the issue. As a result, this update might not be offered to Hyper-V virtual machines running on hosts that utilize certain processor types.”

Those who wish to install the update can now run Windows Update and install it as usual.

However, this update comes with another bug that causes the Taskbar not to display properly if you are using Windows N edition or have the ‘Media Features’ feature turned off in Control Panel > Programs > Programs and Features > Turn Windows features on or off.

Therefore, if you have disabled the Media Features or are running Windows N, which does not contain media-related technologies, you may want to hold off installing the update.

Microsoft is working on fixing both issues and will provide them in an upcoming release.

Sci-Tech

Is T-Mobile still the uncarrier we knew and loved, or just another carrier?

Edgar Cervantes / Android Authority

In 2012, the wireless industry was in a less-than-ideal state. AT&T and Verizon dominated the market, despite a reputation for price gouging. Meanwhile, Sprint and T-Mobile lagged behind in third and fourth place, respectively. In an effort to change its trajectory, T-Mobile hired John Legere as CEO. Legere wasn’t your typical corporate suit. He wore jeans and T-shirts, and cursed like a sailor. He was also outspoken about the poor policies and practices of the larger wireless carriers, and actually made a ton of big changes to the company through the “Uncarrier” marketing initiative.

This campaign aimed to disrupt traditional industry practices, such as two-year contracts, hidden fees, and sudden price increases. These transformations occurred against the backdrop of a planned merger with Sprint, which was finalized in 2020 after extensive negotiations. Fast forward to today, and the new T-Mobile now largely resembles the very companies Legere once vocally opposed.

Is T-mobile still the uncarrier you knew and loved?

64 votes

T-Mobile is starting to look a little like Verizon 2.0

Edgar Cervantes / Android Authority

There were many things T-Mobile criticized its competitors for, but pricing and clarity were chief among Legere’s concerns. In much softer words than he actually used, Legere once essentially accused Verizon and AT&T of being crooks who were taking us for every last cent. That’s just a bit ironic when you consider T-Mobile’s moves over the last few years. While the pandemic naturally drove up pricing, which is more forgivable, T-Mobile’s treatment of legacy customers is not.

First, T-Mobile attempted to automatically shift its legacy customers to newer plans unless the customer specifically contacted them to opt out. When this didn’t work, it ultimately ended up raising legacy pricing anyway, increasing prices by $5 per month per line for voice plans, and $2 per month per line for connected devices. It was also a slap in the face for customers who thought T-Mobile’s earlier Price Lock policies protected them.

T-Mobile used to offer some of the best phone deals, but these days, many of its top free phone offers are typically aimed exclusively at Go5G Plus and Next subscribers. Similarly, T-Mobile Tuesdays used to feature truly great exclusive discounts and promotions for events and much more. This experience has largely devolved into a very limited coupon book app, and many fear this will only worsen with the new T-Life direction.

Those are far from the only changes T-Mobile has made recently that go against the spirit of its Uncarrier movement. In April we learned T-Mobile could be profiling customers and collecting personal data to better predict user behavior. While this is an opt-out feature, I am willing to bet Legere’s T-Mobile would have never even tried something like this.

T-Mobile’s recent price increases and unclear customer changes are exactly the sort of things Legere once criticized Verizon and AT&T for.

Continuing its long line of moves that certainly aren’t customer-first in nature, T-Mobile recently clarified that its pricing could continue to increase, even for Price Lock customers. It also clarified that despite still using the name, T-Mobile customers with a plan from January 17, 2024 are actually on Price Lock 2.0. This newer version will refund you if you cancel due to price increases, but there’s really no promise it won’t continue to jack up prices.

Still not convinced this isn’t the same T-Mobile we all once gushed about? A new bill credits policy might just be enough to put you over the edge. The new policy means you’ll no longer receive bill credits for a free device if you decide to pay off the installment plan early. In other words, if you buy off your plan early, you lose out on your free phone deal.

T-Mobile is likely doing this to prevent customers from paying off a device early and then turning around and selling it for a high price. Before, you could sell the device and remove the installment plan while still receiving any free credits T-Mobile owed you.

All of this shows a carrier that is clearly not concerned with price increases or moves that are seen as less friendly by its existing customer base. This is exactly what Verizon and AT&T have been accused of doing. What makes T-Mobile feel even more like Verizon is that it seems to have set its sights on being the biggest and most powerful carrier.

It’s important to remember the Uncarrier phase was marketing first and foremost

I’ve noticed numerous online comments portraying John Legere as a hero, while Mike Sievert is blamed for T-Mobile’s recent shifts. However, it’s essential to recognize that the Uncarrier movement was primarily a marketing strategy. Legere was hired to revitalize the company, which he effectively did by adopting a relatable image, aggressively cutting costs, and disrupting the industry. But he didn’t do it because he was your friend. These were calculated business decisions.

Legere did his job well, and I respect him for that. However, I also understand how business works. T-Mobile knew that the changes under Legere’s leadership were only a temporary phase. After being promoted to COO, Mike Sievert and John Legere likely developed their strategy extensively. Phase 1 was focused on winning new customers and improving the network to compete with the major carriers. Phase 2 involved tightening the screws to generate real profits and secure T-Mobile’s position as one of the Big Three.

Legere was hired for a job and did it very well. So was Sievert: to make a profit at any cost.

Whether we like it or not, Mike Sievert was also hired for a specific purpose: to take this revitalized company and ensure it remains profitable both now and in the future. He has become the villain by raising prices and ensuring profitability even at the cost of customer satisfaction. It’s a less appealing role, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t doing his job. It’s a delicate balance — maintaining profitability while mitigating potential subscriber losses. T-Mobile likely anticipated some would leave once it was clear that the old Uncarrier days were over, but they planned ahead as best they could by acquiring the most prominent T-Mobile-based carriers.

Our own polls suggest that many of our tech-savvy readers are seriously considering switching to another carrier or even a prepaid service. Those who leave will likely seek coverage at least as good as what they had. If they were satisfied with the Uncarrier’s coverage, switching to Mint or another T-Mobile MVNO is an easy move. For every customer that switches away, a significant portion will still indirectly contribute to T-Mobile’s revenue. T-Mobile also anticipates that major customer losses are less likely among the elderly, large families, or those who are less tech-savvy and hesitant to switch.

Is T-Mobile actually any worse than the other members of the big three?

Edgar Cervantes / Android Authority

The big question is whether T-Mobile is any worse than the other members of the big three, and to answer that, I’d say no. The new T-Mobile actually holds a few strong advantages over the competition. While AT&T and Verizon spread device payments over three whole years, T-Mobile still defaults to 24 months. T-Mobile also offers slightly more competitive pricing, especially for larger families. It also has an increasingly strong and reliable network — customer service and pricing aside. The main takeaway is that it’s no longer the “uncarrier” we once knew; it’s now more just “another member of the big three,” for better or worse.

For many, T-Mobile might still be the best of the big three. However, for most, I’d suggest moving to one of the many excellent prepaid services, which have evolved considerably over the years. Some prepaid carriers, like Google Fi Wireless, offer the same high-quality data, device payment plans, and other features typically associated with postpaid services.

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoMajor African Tribes taken away during the Atlantic Slave Trade🌍 #slavetrade #africanamericanhistory

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoCameroon 🇨🇲 World Cup History (1962-2022) #football #realmadrid #shorts

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Inventors: Mary Kenner 🩸

-

African History4 months ago

African History4 months agoMr Incredible Becoming Canny/Uncanny Mapping (You live in Paraguay 🇵🇾)