World News

Family Values or Fighting Valor? Russia Grapples With Women’s Wartime Role.

The Russian Army is gradually expanding the role of women as it seeks to balance President Vladimir V. Putin’s promotion of traditional family roles with the need for new recruits for the war in Ukraine.

The military’s stepped-up appeal to women includes efforts to recruit female inmates in prisons, replicating on a much smaller scale a strategy that has swelled its ranks with male convicts.

Recruiters in military uniforms toured Russian jails for women in the fall of 2023, offering inmates a pardon and $2,000 a month — 10 times the national minimum wage — in return for serving in frontline roles for a year, according to six current and former inmates of three prisons in different regions of Russia.

Dozens of inmates just from those prisons have signed military contracts or applied to enlist, the women said, a sampling that — along with local media reports about recruitment in other regions — suggests a broader effort to enlist female convicts.

It’s not just convicts. Women now feature in Russian military recruitment advertisements across the country. A pro-Kremlin paramilitary unit fighting in Ukraine also recruits women.

“Combat experience and military specialties are not required,” read an advertisement aimed at women that was posted in March in Russia’s Tatarstan region. It offered training and a sign-up bonus equivalent to $4,000. “We have one goal — victory!”

The Russian military’s need to replenish its ranks for what it presents as a long-term war against Ukraine and its Western allies, however, has clashed with Mr. Putin’s ideological struggle, which portrays Russia as a bastion of social conservatism standing up to the decadent West.

Mr. Putin has placed women at the core of this vision, portraying them as child-bearers, mothers and wives guarding the nation’s social harmony.

“The most important thing for every women, no matter what profession she has chosen and what heights she has reached, is the family,” Mr. Putin said in a speech on March 8.

These clashing military and social priorities have resulted in contradictory policies that seek to recruit women to the military to fill a need, but send conflicting signals about the roles women can assume there.

“I have gotten used to the fact that I am often looked at like a monkey, like, ‘Wow, she’s in fatigues!’” said Ksenia Shkoda, a native of central Ukraine who has fought for pro-Russian forces since 2014.

Some female volunteers do not make it to Ukraine. The convicts who enlisted in late 2023 have yet to be sent to fight, the six former and current inmates said. They spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of possible retribution.

The reason for the delay in their deployment is unknown; the Russian defense ministry and prison service did not respond to requests for comment.

Ms. Shkoda and six other women fighting for Russia in Ukraine said in phone interviews or in written answers to questions that local recruitment offices still routinely turned away female volunteers or sent them to reserves. This occurs even as other officials target them with advertisements to meet broader quotas, underscoring the inherent contradiction in Russia’s recruitment policies.

Tatiana Dvornikova, a Russian sociologist studying prisons for women, believes the Russian Army would delay sending female convicts into battle as long as it has other recruitment options.

“It would create a very unpleasant reputational risk for the Russian Army,” she said, because most Russians would view such a breach of social mores as a sign of desperation.

The Russian Army is on the attack in Ukraine. But its incremental gains have come at very high cost, requiring a constant search for recruits.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, women who wanted to fight for the Kremlin often found their way to the front through militias in the east of Ukraine, rather than regular forces. These separatist units were chronically understaffed after a decade of smaller-scale conflict against Kyiv.

“They accepted anyone — absolutely anyone,” said Anna Ilyasova, who grew up in Ukraine’s Donetsk region and joined the local separatist militia days before Russia’s full-scale invasion. “I couldn’t even hold an automatic rifle.”

After serving in combat, Ms. Ilyasova now works as a political officer in a regular Russian battalion fighting in Ukraine.

Other women joined a Russian paramilitary unit started by soccer hooligans, called Española. It opened its ranks to women in September 2022, and has published recruitment videos publicizing their combat roles.

“These people take care of me, they are like a family,” said an Española fighter from Crimea who goes by the call sign Poshest, meaning “Plague.” She has fought with Española since 2022 as a medic, sniper and airplane pilot.

All of the interviewed female soldiers said women remained rare in their units, outside medical roles.

Russia’s cautious approach to women’s participation in the military differs from the more liberal policy adopted by Ukraine.

The number of women serving in Ukrainian military has risen by 40 percent since the invasion, reaching 43,000 in late 2023, according the country’s defense ministry. After the invasion, the Ukrainian military abolished gender restrictions on many combat roles.

The much larger Russian military also had about 40,000 servicewomen before the war. The majority, however, have served in administrative roles.

For both Russia and Ukraine, the military opportunities available to women have long fluctuated with recruitment needs.

The Russian Empire, which included most of modern Ukraine, created its first female combat units toward the end of World War I, after years of heavy losses. Decades later, the Soviet Union became the first country to call up women for combat, to compensate for the millions of casualties suffered in the first year of the Nazi invasion.

The lionization of female snipers and fighter pilots in World War II, however, masked the discrimination and sexual abuse many women faced as soldiers. The discrimination has continued into the modern era, exemplified by the way Russian women have struggled to collect the military benefits for their service in the Afghanistan War.

In Ukraine, the majority of Russian female soldiers interviewed for this article denied facing open discrimination. But some described male peers who felt the need to protect them, echoing the country’s traditional gender roles.

“My constant urge to throw myself into the thick of the battle is often halted with arguments like: ‘But you’re a girl!’” said Ms. Shkoda, the pro-Russian soldier. “And this drives me absolutely mad.”

Ms. Ilyasova, the Russian Army officer, said she had repeatedly turned down marriage proposals from a man in her unit.

“I always say that I’m married to war” to deflect the unwanted romantic attention, Ms. Ilyasova added.

Ruslan Pukhov, a Moscow-based security analyst who sits on the defense ministry’s advisory council, said the Russian Army had been trying to recruit more women for rear-guard roles such as mechanics and administrators for years, because they are viewed as hard workers who drink less.

The idea of using women in combat begun to gain supporters among generals following Russia’s intervention in the Syrian civil war in 2015, which brought them in contact with the disciplined women fighters of the Kurd militias, Mr. Pukhov said.

The invasion of Ukraine in 2022, has brought the idea to the fore, leading Russia to consider the military potential of about 40,000 women who were imprisoned in the country in the first year of the war.

Prison officials started compiling lists of inmates with medical training in at least some jails for women soon after the invasion. The six current and former inmates said they were not told the purpose of the medical lists, but assumed that they were a shortlist for military recruitment.

Then, in autumn of 2023, men in military uniforms visited each of the two prisons twice, the inmates said. They offered women contracts to be trained to serve as snipers, combat medics or radio operators. In another female prison, in the Ural Mountains, officials put up the recruitment offer on the bulletin board, and asked interested inmates to write a petition to join the army.

“Everyone wanted to go, because, despite everything, it’s still freedom,” said Yulia, who said she applied to join the army while serving a sentence for murder. “Either I would die, or I would buy an apartment.”

Dozens of women in the three colonies, which were all in the European part of Russia, accepted the offer, the six current and former inmates said.

In interviews, these women cited enlistment motives similar to those of male convicts: freedom, money and regaining their sense of self-worth. The reality of Russian prisons for women, however, accentuated these needs.

Female inmates in Russia are subject to stricter rules and more compulsory labor than men. And on their release, they face even greater social isolation, because apart from breaking the law, they shatter the Russian society’s image of women’s behavior, said Ms. Dvornikova, the sociologist.

That was the experience of one inmate named Maria, who said she had enlisted to fight in Ukraine with just months to go on her sentence for theft. She took the risk because the pardon would erase her criminal record, allowing her to provide for her daughter if she survived.

But after signing the military contract late last year, Maria said she and other volunteers from her jail have not been called up, and she struggled to keep a job once her employers discovered her previous criminal record.

Maria said she eventually found informal work as a seamstress, but would still go to war if called up.

In jail, “all we cared about was for them to take us away, and send us to fight,” said Maria. “I will be in the recruitment office the next day, if I hear that the process got underway.”

Reporting was contributed by Oleg Matsnev, Alina Lobzina, Andrew E. Kramer and Carlotta Gall.

World News

University of Pennsylvania police arrest anti-Israel agitators on campus

Several anti-Israel agitators were arrested at the University of Pennsylvania on Friday night after hundreds of protesters descended into a campus building and attempted to occupy it.

Police confirmed to Fox News Digital that there were multiple arrests at the university’s Fisher Bennett Hall on Friday night. It is unknown at this time how many were arrested.

The UPenn Police Department announced in a community notice that a “large disorderly crowd” began gathering at 8 p.m. on Friday, and moved into Fisher Bennett Hall on the university’s campus and attempted to occupy it.

Law enforcement advised students to “avoid the immediate area.”

Pro-Palestinian protestors stage an encampment at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States April 25, 2024. (Getty Images)

Campus police, along with assistance from the Philadelphia Police Department, escorted the protesters from the campus building.

In an 11 p.m. update, authorities said that the protesters had dispersed.

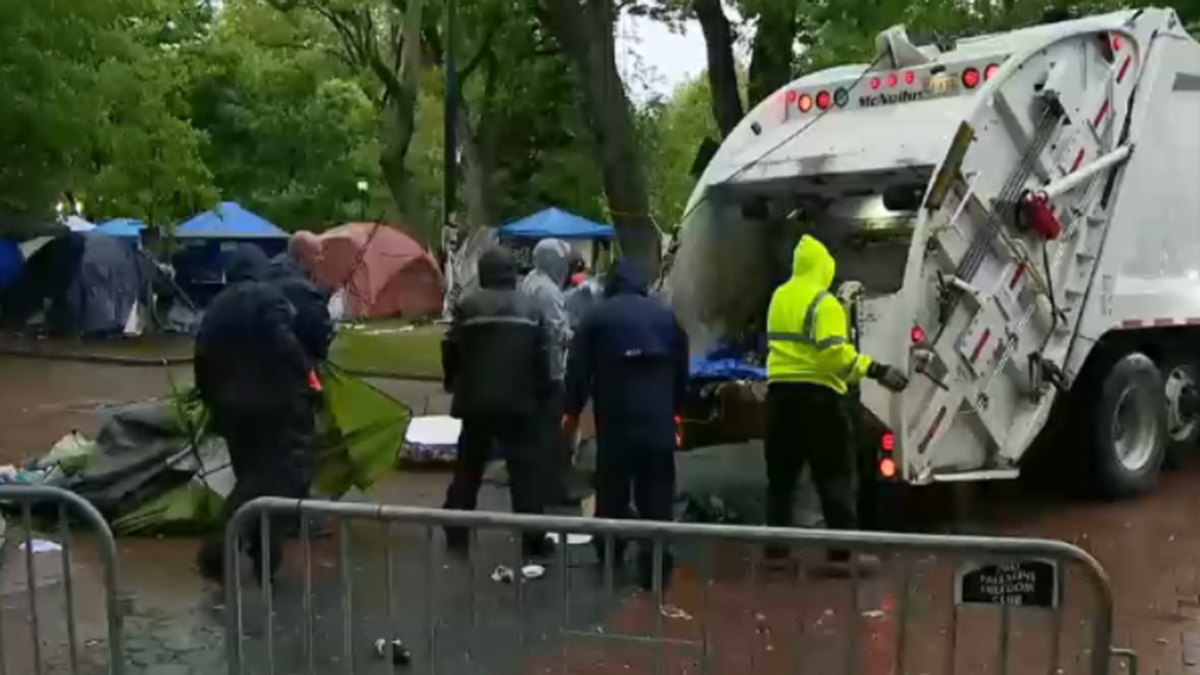

An anti-Israel encampment is removed Friday at the University of Pennsylvania campus in Philadelphia. (WTXF)

The occupation came one week after police dismantled an encampment that had taken over part of the Ivy League’s campus for two weeks.

In a statement, members of the Penn Gaza Solidarity Encampment accused the University of Penn administration of not negotiating with them in good faith over “Penn’s investment with Israel.”

World News

Being Muslim in Modi’s India

It is a lonely feeling to know that your country’s leaders do not want you. To be vilified because you are a Muslim in what is now a largely Hindu-first India.

It colors everything. Friends, dear for decades, change. Neighbors hold back from neighborly gestures — no longer joining in celebrations, or knocking to inquire in moments of pain.

“It is a lifeless life,” said Ziya Us Salam, a writer who lives on the outskirts of Delhi with his wife, Uzma Ausaf, and their four daughters.

When he was a film critic for one of India’s main newspapers, Mr. Salam, 53, used to fill his time with cinema, art, music. Workdays ended with riding on the back of an older friend’s motorcycle to a favorite food stall for long chats. His wife, a fellow journalist, wrote about life, food and fashion.

Now, Mr. Salam’s routine is reduced to office and home, his thoughts occupied by heavier concerns. The constant ethnic profiling because he is “visibly Muslim” — by the bank teller, by the parking lot attendant, by fellow passengers on the train — is wearying, he said. Family conversations are darker, with both parents focused on raising their daughters in a country that increasingly questions or even tries to erase the markers of Muslims’ identity — how they dress, what they eat, even their Indianness altogether.

One of them, an impressive student-athlete, struggled so much that she needed counseling and missed months of school. The family often debates whether to stay in their mixed Hindu-Muslim neighborhood in Noida, just outside Delhi. Mariam, their oldest daughter, who is a graduate student, leans toward compromise, anything to make life bearable. She wants to move.

Anywhere but a Muslim area might be difficult. Real estate agents often ask outright if families are Muslim; landlords are reluctant to rent to them.

“I have started taking it in stride,” Mariam said.

“I refuse to,” Mr. Salam shot back. He is old enough to remember when coexistence was largely the norm in an enormously diverse India, and he does not want to add to the country’s increasing segregation.

But he is also pragmatic. He wishes Mariam would move abroad, at least while the country is like this.

Mr. Salam clings to the hope that India is in a passing phase.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, however, is playing a long game.

His rise to national power in 2014, on a promise of rapid development, swept a decades-old Hindu nationalist movement from the margins of Indian politics firmly to the center. He has since chipped away at the secular framework and robust democracy that had long held India together despite its sometimes explosive religious and caste divisions.

Right-wing organizations began using the enormous power around Mr. Modi as a shield to try to reshape Indian society. Their members provoked sectarian clashes as the government looked away, with officials showing up later to raze Muslim homes and round up Muslim men. Emboldened vigilante groups lynched Muslims they accused of smuggling beef (cows are sacred to many Hindus). Top leaders in Mr. Modi’s party openly celebrated Hindus who committed crimes against Muslims.

On large sections of broadcast media, but particularly on social media, bigotry coursed unchecked. WhatsApp groups spread conspiracy theories about Muslim men luring Hindu women for religious conversion, or even about Muslims spitting in restaurant food. While Mr. Modi and his party officials reject claims of discrimination by pointing to welfare programs that cover Indians equally, Mr. Modi himself is now repeating anti-Muslim tropes in the election that ends early next month. He has targeted India’s 200 million Muslims more directly than ever, calling them “infiltrators” and insinuating that they have too many children.

This creeping Islamophobia is now the dominant theme of Mr. Salam’s writings. Cinema and music, life’s pleasures, feel smaller now. In one book, he chronicled the lynchings of Muslim men. In a recent follow-up, he described how India’s Muslims feel “orphaned” in their homeland.

“If I don’t pick up issues of import, and limit my energies to cinema and literature, then I won’t be able to look at myself in the mirror,” he said. “What would I tell my kids tomorrow — when my grandchildren ask me what were you doing when there was an existential crisis?”

As a child, Mr. Salam lived on a mixed street of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims in Delhi. When the afternoon sun would grow hot, the children would move their games under the trees in the yard of a Hindu temple. The priest would come with water for all.

“I was like any other kid for him,” Mr. Salam recalled.

Those memories are one reason Mr. Salam maintains a stubborn optimism that India can restore its secular fabric. Another is that Mr. Modi’s Hindu nationalism, while sweeping large parts of the country, has been resisted by several states in the country’s more prosperous south.

Family conversations among Muslims there are very different: about college degrees, job promotions, life plans — the usual aspirations.

In the state of Tamil Nadu, often-bickering political parties are united in protecting secularism and in focusing on economic well-being. Its chief minister, M.K. Stalin, is a declared atheist.

Jan Mohammed, who lives with his family of five in Chennai, the state capital, said neighbors joined in each other’s religious celebrations. In rural areas, there is a tradition: When one community finishes building a place of worship, villagers of other faiths arrive with gifts of fruits, vegetables and flowers and stay for a meal.

“More than accommodation, there is understanding,” Mr. Mohammed said.

His family is full of overachievers — the norm in their educated state. Mr. Mohammed, with a master’s degree, is in the construction business. His wife, Rukhsana, who has an economics degree, started an online clothing business after the children grew up. One daughter, Maimoona Bushra, has two master’s degrees and now teaches at a local college as she prepares for her wedding. The youngest, Hafsa Lubna, has a master’s in commerce and within two years went from an intern at a local company to a manager of 20.

Two of the daughters had planned to continue on to Ph.D’s. The only worry was that potential grooms would be intimidated.

“The proposals go down,” Ms. Rukhsana joked.

A thousand miles north, in Delhi, Mr. Salam’s family lives in what feels like another country. A place where prejudice has become so routine that even a friendship of 26 years can be sundered as a result.

Mr. Salam had nicknamed a former editor “human mountain” for his large stature. When they rode on the editor’s motorcycle after work in the Delhi winter, he shielded Mr. Salam from the wind.

They were together often; when his friend got his driver’s license, Mr. Salam was there with him.

“I would go to my prayer every day, and he would go to the temple every day,” Mr. Salam said. “And I used to respect him for that.”

A few years ago, things began to change. The WhatsApp messages came first.

The editor started forwarding to Mr. Salam some staples of anti-Muslim misinformation: for example, that Muslims will rule India in 20 years because their women give birth every year and their men are allowed four wives.

“Initially, I said, ‘Why do you want to get into all this?’ I thought he was just an old man who was getting all these and forwarding,” Mr. Salam said. “I give him the benefit of doubt.”

The breaking point came two years ago, when Yogi Adityanath, a Modi protégé, was re-elected as the leader of Uttar Pradesh, the populous state adjoining Delhi where the Salam family lives. Mr. Adityanath, more overtly belligerent than Mr. Modi toward Muslims, governs in the saffron robe of a Hindu monk, frequently greeting large crowds of Hindu pilgrims with flowers, while cracking down on public displays of Muslim faith.

On the day of the vote counting, the friend kept calling Mr. Salam, rejoicing at Mr. Adityanath’s lead. Just days earlier, the friend had been complaining about rising unemployment and his son’s struggle to find a job during Mr. Adityanath’s first term.

“I said, ‘You have been so happy since morning, what do you gain?’” he recalled asking the friend.

“Yogi ended namaz,” the friend responded, referring to Muslim prayer on Fridays that often spills into the streets.

“That was the day I said goodbye,” Mr. Salam said, “and he hasn’t come back into my life after that.”

World News

Slack Is Using Your Private Conversations to Train Its AI

Slack users across the web—on Mastodon, on Threads, and on Hackernews—have responded with alarm to an obscure privacy page that outlines the ways in which their Slack conversations, including DMs, are used to train what the Salesforce-owned company calls “Machine Learning” (ML) and “Artificial Intelligence” (AI) systems. The only way to opt out of these features is for the admin of your company’s Slack setup to send an email to Slack requesting it be turned off.

The policy, which applies to all Slack instances—not just those that have opted into the Slack AI add-on—states that Slack systems “analyze Customer Data (e.g. messages, content and files) submitted to Slack as well as Other Information (including usage information) as defined in our privacy policy and in your customer agreement.”

So, basically, everything you type into Slack is used to train these systems. Slack states that data “will not leak across workspaces” and that there are “technical controls in place to prevent access.” Even so, we all know that conversations with AI chatbots are not private, and it’s not hard to imagine this going wrong somehow. Given the risk, the company must be offering something extremely compelling in return…right?

What are the benefits of letting Slack use your data to train AI?

The section outlining the potential benefits of Slack feeding all of your conversations into a large language model says this will allow the company to provide improved search results, better autocomplete suggestions, better channel recommendations, and (I wish I was kidding) improved emoji suggestions. If this all sounds useful to you, great! I personally don’t think any of these things—except possibly better search—will do much to make Slack more useful for getting work done.

The emoji thing, particularly, is absurd. Slack is literally saying that they need to feed your conversations into an AI system so that they can provide better emoji recommendations. Consider this actual quote, which I promise you is from Slack’s website and not The Onion:

Slack might suggest emoji reactions to messages using the content and sentiment of the message, the historic usage of the emoji and the frequency of use of the emoji in the team in various contexts. For instance, if 🎉 is a common reaction to celebratory messages in a particular channel, we will suggest that users react to new, similarly positive messages with 🎉.

I am overcome with awe just thinking about the implications of this incredible technology, and am no longer concerned about any privacy implications whatsoever. AI is truly the future of communication.

How to opt your company out of Slack’s AI training

The bad news is that you, as an individual user, cannot opt out of Slack using your conversation history to train its large language model. That can only be done by a Slack admin, which in most cases is going to be someone in the IT department of your company. And there’s no button in the settings for opting out—admins need to send an email asking for it to happen.

Here’s Slack exact language on the matter:

If you want to exclude your Customer Data from Slack global models, you can opt out. To opt out, please have your org, workspace owners or primary owner contact our Customer Experience team at [email protected] with your workspace/org URL and the subject line ‘Slack global model opt-out request’. We will process your request and respond once the opt-out has been completed.

This smells like a dark pattern—making something annoying to do in order to discourage people from doing it. Hopefully the company makes the opt-out process easier in the wake of the current earful they’re getting from customers.

A reminder that Slack DMs aren’t private

I’ll be honest, I’m a little amused at the prospect of my Slack data being used to improve search and emoji suggestions for my former employers. At previous jobs, I frequently sent DMs to work friends filled with negativity about my manager and the company leadership. I can just picture Slack recommending certain emojis every time a particular CEO is mentioned.

Funny as that idea is, though, the whole situation serves as a good reminder to employees everywhere: Your Slack DMs aren’t actually private. Nothing you say on Slack—even in a direct message—is private. Slack uses that information to train tools like this, yes, but the company you work for can also access those private messages pretty easily. I highly recommend using something not controlled by your company if you need to shit talk said company. Might I suggest Signal?

-

African History4 months ago

African History4 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History4 years ago

African History4 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History2 years ago

African History2 years agoHow Did Normal Medieval People Survive Winter? | Tudor Monastery Farm | Chronicle

-

African History3 years ago

African History3 years agoThe Entire History of Africa in Under 10 Minutes – Documentary

-

African History4 years ago

African History4 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History3 years ago

African History3 years agoWhat happened to the many African Kingdoms? History of Africa 1500-1800 Documentary 1/6

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoA Black African King in Medieval European Art