Sci-Tech

The Voices of A.I. Are Telling Us a Lot

What does artificial intelligence sound like? Hollywood has been imagining it for decades. Now A.I. developers are cribbing from the movies, crafting voices for real machines based on dated cinematic fantasies of how machines should talk.

Last month, OpenAI revealed upgrades to its artificially intelligent chatbot. ChatGPT, the company said, was learning how to hear, see and converse in a naturalistic voice — one that sounded much like the disembodied operating system voiced by Scarlett Johansson in the 2013 Spike Jonze movie “Her.”

ChatGPT’s voice, called Sky, also had a husky timbre, a soothing affect and a sexy edge. She was agreeable and self-effacing; she sounded like she was game for anything. After Sky’s debut, Johansson expressed displeasure at the “eerily similar” sound, and said that she had previously declined OpenAI’s request that she voice the bot. The company protested that Sky was voiced by a “different professional actress,” but agreed to pause her voice in deference to Johansson. Bereft OpenAI users have started a petition to bring her back.

A.I. creators like to highlight the increasingly naturalistic capabilities of their tools, but their synthetic voices are built on layers of artifice and projection. Sky represents the cutting edge of OpenAI’s ambitions, but she is based on an old idea: of the A.I. bot as an empathetic and compliant woman. Part mommy, part secretary, part girlfriend, Samantha was an all-purpose comfort object who purred directly into her users’ ears. Even as A.I. technology advances, these stereotypes are re-encoded again and again.

Women’s voices, as Julie Wosk notes in “Artificial Women: Sex Dolls, Robot Caregivers, and More Facsimile Females,” have often fueled imagined technologies before they were built into real ones.

In the original “Star Trek” series, which debuted in 1966, the computer on the deck of the Enterprise was voiced by Majel Barrett-Roddenberry, the wife of the show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry. In the 1979 film “Alien,” the crew of the USCSS Nostromo addressed its computer voice as “Mother” (her full name was MU-TH-UR 6000). Once tech companies started marketing virtual assistants — Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Cortana — their voices were largely feminized, too.

These first-wave voice assistants, the ones that have been mediating our relationships with technology for more than a decade, have a tinny, otherworldly drawl. They sound auto-tuned, their human voices accented by a mechanical trill. They often speak in a measured, one-note cadence, suggesting a stunted emotional life.

But the fact that they sound robotic deepens their appeal. They come across as programmable, manipulatable and subservient to our demands. They don’t make humans feel as if they’re smarter than we are. They sound like throwbacks to the monotone feminine computers of “Star Trek” and “Alien,” and their voices have a retro-futuristic sheen. In place of realism, they serve nostalgia.

That artificial sound has continued to dominate, even as the technology behind it has advanced.

Voice-to-speech software was designed to make visual media accessible to users with certain disabilities, and on TikTok, it has become a creative force in its own right. Since TikTok rolled out its text-to-speech feature, in 2020, it has developed a host of simulated voices to choose from — it now offers more than 50, including ones named “Hero,” “Story Teller” and “Bestie.” But the platform has come to be defined by one option. “Jessie,” a relentlessly pert woman’s voice with a slightly fuzzy robotic undertone, is the mindless voice of the mindless scroll.

Jessie seems to have been assigned a single emotion: enthusiasm. She sounds as if she is selling something. That’s made her an appealing choice for TikTok creators, who are selling themselves. The burden of representing oneself can be outsourced to Jessie, whose bright, retro robot voice lends videos a pleasantly ironic sheen.

Hollywood has constructed masculine bots, too — none more famous than HAL 9000, the computer voice in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Like his feminized peers, HAL radiates serenity and loyalty. But when he turns against Dave Bowman, the film’s central human character — “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that” — his serenity evolves into a frightening competence. HAL, Dave realizes, is loyal to a higher authority. HAL’s masculine voice allows him to function as a rival and a mirror to Dave. He is allowed to become a real character.

Like HAL, Samantha of “Her” is a machine who becomes real. In a twist on the Pinocchio story, she starts the movie tidying a human’s email inbox and ends up ascending to a higher level of consciousness. She becomes something even more advanced than a real girl.

Scarlett Johansson’s voice, as inspiration for bots both fictional and real, subverts the vocal trends that define our feminized helpmeets. It has a gritty edge that screams I am alive. It sounds nothing like the processed virtual assistants we are accustomed to hearing speaking through our phones. But her performance as Samantha feels human not just because of her voice but because of what she has to say. She grows over the course of the film, acquiring sexual desires, advanced hobbies and A.I. friends. In borrowing Samantha’s affect, OpenAI made Sky seem as if she had a mind of her own. Like she was more advanced than she really was.

When I first saw “Her,” I thought only that Johansson had voiced a humanoid bot. But when I revisited the film last week, after watching OpenAI’s ChatGPT demo, the Samantha role struck me as infinitely more complex. Chatbots do not spontaneously generate human speaking voices. They don’t have throats or lips or tongues. Inside the technological world of “Her,” the Samantha bot would have itself been based on the voice of a human woman — perhaps a fictional actress who sounds much like Scarlett Johansson.

It seemed that OpenAI had trained its chatbot on the voice of a nameless actress who sounds like a famous actress who voiced a movie chatbot implicitly trained on an unreal actress who sounds like a famous actress. When I run ChatGPT’s demo, I am hearing a simulation of a simulation of a simulation of a simulation of a simulation.

Tech companies advertise their virtual assistants in terms of the services they provide. They can read you the weather report and summon you a taxi; OpenAI promises that its more advanced chatbots will be able to laugh at your jokes and sense shifts in your moods. But they also exist to make us feel more comfortable about the technology itself.

Johansson’s voice functions like a luxe security blanket thrown over the alienating aspects of A.I.-assisted interactions. “He told me that he felt that by my voicing the system, I could bridge the gap between tech companies and creatives and help consumers to feel comfortable with the seismic shift concerning humans and A.I.,” Johansson said of Sam Altman, OpenAI’s founder. “He said he felt that my voice would be comforting to people.”

It is not that Johansson’s voice sounds inherently like a robot’s. It’s that developers and filmmakers have designed their robots’ voices to ease the discomfort inherent in robot-human interactions. OpenAI has said that it wanted to cast a chatbot voice that is “approachable” and “warm” and “inspires trust.” Artificial intelligence stands accused of devastating the creative industries, guzzling energy and even threatening human life. Understandably, OpenAI wants a voice that makes people feel at ease using its products. What does artificial intelligence sound like? It sounds like crisis management.

OpenAI first rolled out Sky’s voice to premium members last September, along with another feminine voice called Juniper, the masculine voices Ember and Cove, and a voice styled as gender-neutral called Breeze. When I signed up for ChatGPT and said hello to its virtual assistant, a man’s voice piped up in Sky’s absence. “Hi there. How’s it going?” he said. He sounded relaxed, steady and optimistic. He sounded — I’m not sure how else to describe it — handsome.

I realized that I was speaking with Cove. I told him that I was writing an article about him, and he flattered my work. “Oh, really?” he said. “That’s fascinating.” As we spoke, I felt seduced by his naturalistic tics. He peppered his sentences with filler words, like “uh” and “um.” He raised his voice when he asked me questions. And he asked me a lot of questions. It felt as if I was talking with a therapist, or a dial-a-boyfriend.

But our conversation quickly stalled. Whenever I asked him about himself, he had little to say. He was not a character. He had no self. He was designed only to assist, he informed me. I told him I would speak to him later, and he said, “Uh, sure. Reach out whenever you need assistance. Take care.” It felt as if I had hung up on an actual person.

But when I reviewed the transcript of our chat, I could see that his speech was just as stilted and primitive as any customer service chatbot. He was not particularly intelligent or human. He was just a decent actor making the most of a nothing role.

When Sky disappeared, ChatGPT users took to the company’s forums to complain. Some bristled at their chatbots defaulting to Juniper, who sounded to them like a “librarian” or a “Kindergarten teacher” — a feminine voice that conformed to the wrong gender stereotypes. They wanted to dial up a new woman with a different personality. As one user put it: “We need another female.”

Produced by Tala Safie

Audio via Warner Bros. (Samantha, HAL 9000); OpenAI (Sky); Paramount Pictures (Enterprise Computer); Apple (Siri); TikTok (Jessie)

Sci-Tech

Would having an AI boss be better than your current human one?

By MaryLou Costa, Business reporter

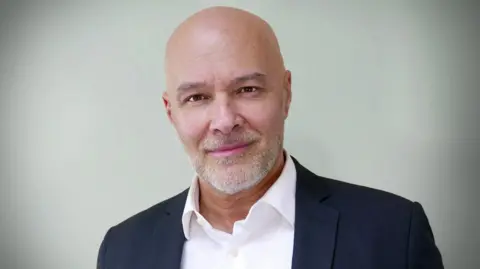

Hannu Rauma

Hannu RaumaWith the stress of managing 83 employees taking its toll, Hannu Rauma was feeling discouraged and frustrated.

“I was getting too bogged down in all these things that were going wrong amongst the teams, and feeling this disappointment,” says Mr Rauma, who is based in Vancouver, Canada.

He is a senior manager at a company called Student Marketing Agency, which employs university students to provide marketing support for small businesses.

“When I was bringing new clients on board, half of my mind would be saying, ‘we’re going to screw up’, and it would dampen my enthusiasm.”

But Mr Rauma says that all changed from last November, when the firm began using an autonomous AI manager developed by US-based company Inspira.

The AI manager helps the agency’s employees, who work flexible hours remotely, to set their schedules and plan their workloads in advance.

It checks their timekeeping, sends them deadline reminders and regular check-in messages, and records the time spent on different clients, so the latter can be billed accurately. The AI also makes suggestions to improve the wording of written text, is available to answer work-related questions, and automatically updates everyone’s work progress in a central portal.

Mr Rauma says that the shift towards an AI manager has not only reduced his stress levels, but has enabled his employees to work faster and be more productive. “I’m able to focus on the growth of the company and all the positive things. It’s added years to my life, I’m sure,” he says.

Mr Rauma adds that his relationships with his employees have also improved drastically. “Before, it felt a lot like a father-child situation. Now, we’re more on an equal footing. Before, it was only about solving problems. But now we’re able to have more light-hearted discussions.”

But not everyone at Student Marketing Agency is using the AI manager yet. Mr Rauma and 26 of his 83 employees were actually part of a study run by Inspira and academics from Columbia University, Arizona State University, and the University of Wisconsin to compare the performance of the AI manager with its human counterparts.

Participants were divided into three groups: one coached by a human manager, another by the AI manager, and the last group by both AI and human manager.

The AI manager achieved a 44% success rate in getting employees to pre-plan their workdays in advance, and was able to motivate the employees to log in on time 42% of the time. These figures were comparable to the human manager, who achieved scores of 45% and 44% for those two areas.

Yet when the AI manager worked in partnership with a human manager, together they achieved a 72% success rate in getting employees to pre-plan their workdays, and managed to achieve 46% on-time success.

Despite the study being statistically small, and concentrated on a specific type of worker and field, its results point to interesting implications for companies introducing AI tools.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile businesses like UPS, Klarna, Dell and others have announced significant job cuts this year, with the intention of replacing many roles with AI, Prof Paul Thurman, from Columbia University in New York, argues that swapping management roles completely for AI would be a mistake.

“The middle management layer is the most critical layer in any organisation,” says the professor of management. “They’re the layer that, if it starts turning over, you’re in for a wild ride. Your people don’t see continuity, they don’t get mentoring and coaching… all the human things that human managers are better at than AI and should be focusing on.”

AI, Prof Thurman adds, can liberate managers from endless reminding and checking in, to focus on more innovative ways of working. For example, managers can cherry pick project teams based on individual skillsets, oversee the brief, then hand over to their AI to manage minutiae like deadlines.

AI can also identify who in the team is falling behind and may need to be managed more closely by a human, and by the same token, hone in on star performers who require extra recognition.

But companies should steer away from AI managers becoming a surveillance tool, he says.

“You don’t want to get to a point where you are noting that, not only do people not clock in on time, but they take too much time at lunch, and they’re not eating enough salad. You don’t want to go that far,” says Prof Thurman. “You want to find the right way to encourage the right behaviours.”

AI managers can also help people who have become “accidental managers” – people who excel in their roles and end up managing people as a result, despite management not being a natural skill for them, says Tina Rahman, founder of London-based HR consultancy, HR Habitat.

“We did a study which looked at the reasons people leave a job. Almost 100% of the respondents said it was because of bad management.

“Some of them said they didn’t like the way they’d been managed, and most of them also said it was because they didn’t know what was expected of them or if they were doing a good job,” says Ms Rahman.

“You’d assume that an AI manager would be built to give those correct instructions, to give complete transparency on the requirements, and the outcomes. People are likely to be more productive when they know what’s expected of them.”

But an over-reliance on AI management sets the tone that companies only care about output and not people, Ms Rahman warns.

“It’s going to be very hard for a business to tell their employees that they’re introducing this brand new AI system that’s going to completely manage them, then say, with the same face, that ‘we care about your experiences in the workplace,’” she says.

James Bore

James BoreYet perhaps the biggest concern about AI managers is not from a people perspective, but from a cybersecurity one, warns James Bore, managing director of cybersecurity consultancy, Bores, and speaker and author.

“If you have an AI manager, and you’ve given them all of the company’s processes, procedures, and intellectual property that is suddenly all in the software, it can be kidnapped by someone who wants to clone it, and it could also be held to ransom,” says Mr Bore.

“If you’ve come to rely on it, which companies will when they start replacing humans with AI, you’re kind of stuck, because you’ve got no resilience, no option to switch back to the humans, because you don’t have them anymore.”

Rather than companies becoming more efficient through an extensive use of AI, Mr Bore says there could be an unintended consequence beyond becoming dependent on systems that could fail.

“The more you automate, and the more you remove people from your business, yes, you’ll bring down costs. But you will also make your company more replaceable.”

Sci-Tech

Judge Backs Challenge to F.T.C.’s Noncompete Ban, at Least for Now

A federal judge on Wednesday backed an initial legal challenge to the Federal Trade Commission’s ban on noncompete agreements, which is scheduled to take effect in September.

Judge Ada Brown granted an injunction requested by several plaintiffs, saying the ban cannot be enforced against them pending a final ruling.

But while the ruling is preliminary, she said that the F.T.C. lacked “substantive rule-making authority” with respect to unfair methods of competition and that the plaintiffs were “likely to succeed on the merits” of their challenge.

Judge Brown, of U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, said she expected to issue a final decision by the end of August.

The commission “stands by our clear authority, supported by statute and precedent, to issue this rule,” said Douglas Farrar, an F.T.C. spokesman. He added that the agency would “keep fighting” noncompetes in an effort to promote worker mobility and economic growth.

In April, the tax firm Ryan L.L.C. sued to block the near-total ban on noncompetes, just hours after the F.T.C. voted 3 to 2 to adopt the rule. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce later joined the case as a plaintiff, as did the Business Roundtable and two Texas business groups.

Banning noncompete agreements, which prohibit workers from switching jobs within an industry, would increase workers’ earnings by at least $400 billion over the next decade, the F.T.C. estimates. The agreements affect roughly one in five American workers, or around 30 million people, according to the agency, whose purview includes antitrust and consumer protection issues.

“If you’re not working in the most productive place you could be working because of a noncompete, that’s a loss for the economy,” Aviv Nevo, director of the F.T.C.’s Bureau of Economics, said at a conference in April.

Business groups argue that the ban would limit their ability to protect trade secrets and confidential information. The Chamber of Commerce and other groups assert that the F.T.C. lacks constitutional and statutory authority to adopt its proposed rule, with Ryan L.L.C. calling it “arbitrary, capricious, and otherwise unlawful.” Another lawsuit seeking to block the rule is pending in federal court in Pennsylvania.

But the three Democrats on the five-member commission maintain that it can legally issue rules defining unfair methods of competition under the F.T.C. Act of 1914, the law that created the agency. Their position has garnered some bipartisan support, too: Representative Matt Gaetz, Republican of Florida, argued in a brief filed in the Texas case that the noncompete ban falls “squarely within” the rule-making authority granted to the commission by Congress.

The Supreme Court’s decision last week to limit the broad regulatory power of federal agencies could raise the agency’s legal hurdles.

Mark Goldstein, a labor and employment lawyer at Reed Smith in New York, said that while limited to only the plaintiffs at this stage, Judge Brown’s injunction was a strong indication that she would deem the F.T.C.’s rule invalid, preventing it from going into effect nationwide.

“The writing is on the wall there,” Mr. Goldstein said. “I have never seen a court issue a preliminary injunction and then, absent some extremely unusual circumstances, issue a final decision that wasn’t consistent with the preliminary injunction.”

As litigation over the noncompete rule drags on, some lawyers are already advising employers to start relying more heavily on different agreements to protect trade secrets and business interests.

In a blog post after the F.T.C. adopted its noncompete ban, the law firm Winston & Strawn suggested that employers adopt alternative measures, such as narrowly tailored nondisclosure agreements and requirements that employees repay the company for training costs if they leave before a set period — known as training repayment agreement provisions, or TRAPs.

“Focus on these additional protections has become greater,” said Kevin Goldstein, an antitrust partner at Winston & Strawn.

But even those agreements are under increasing scrutiny. The commission’s final rule encompasses “de facto noncompetes” — measures that, in effect, prevent a worker from switching jobs within an industry, even if they aren’t labeled noncompete clauses. And employers are eyeing the shifting landscape of state and federal restrictions on such covenants, including nondisclosure agreements, beyond the F.T.C.’s rule.

While the commission’s vote to ban noncompetes has garnered the most attention, moves from other federal agencies and state legislatures against agreements that restrict worker mobility are simultaneously on the rise.

“There’s been increased hostility toward these agreements in general, across the country,” said Christine Bestor Townsend, co-chair of the unfair competition and trade secrets practice group at Ogletree Deakins.

Last month, a National Labor Relations Board judge ruled for the first time that a noncompete clause is an unfair labor practice, as part of her decision in an unfair-termination case. The judge also broke new ground by barring a nonsolicitation clause, which restricts soliciting clients or employees of a former employer; she argued that both types of agreements could chill protected activity, including union organizing.

That ruling followed a memo last year from the labor board’s general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, that clarified her view that noncompete provisions in employment contracts violate the National Labor Relations Act, except in limited circumstances.

“It’s one thing to get a guidance memo from the general counsel, which is significant and important,” said Jonathan F. Harris, an associate professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles who studies contracts and employment law. “And it’s another thing to see the adjudication side of the N.L.R.B. agree with her.”

These kinds of restrictive covenants tend to scare workers away from labor organizing, Mr. Harris said, “because the consequences of being fired for organizing become that much greater if you can’t get another job afterwards.”

Other federal agencies have jumped in as well, eyeing a range of employment provisions that they argue unfairly constrain workers. It’s part of the whole-of-government approach by the Biden administration to what it considers anticompetitive restraints on worker mobility.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, for example, issued a report last summer on the dangers of provisions requiring workers to repay training costs if they leave a job before a certain time elapses.

It’s not just a federal push: State governments are also stepping in to promote worker mobility — a trend that was in motion before the F.T.C. voted to ban noncompetes in April, but one that has gained momentum since.

Last month, the Rhode Island legislature passed a bill to ban noncompetes, joining Minnesota, California, Oklahoma and North Dakota. Dozens more states have enacted partial restrictions.

“Minnesota didn’t turn into a gaping crater,” said Pat Garofalo, the director of state and local policy at the American Economic Liberties Project, a progressive think tank, referring to the state’s wide-reaching ban on noncompetes that went into effect last year. “Once a domino falls over, a bunch of other dominoes fall over after.”

State laws can also prove more resilient to challenges than federal rules.

“State legislatures obviously have a lot of interest in getting these rules on the books right now,” Mr. Garofalo said.

Sci-Tech

How Tom Hanks’s Son Spawned a Hateful Meme Online

In the spring of 2021, Chet Hanks, the singer, actor and son of Tom, posted a series of statements and a music video with a refrain that caused confusion, not to mention a fair bit of cringing. He declared it was going to be a “white boy summer.”

Whatever exactly he meant at the time, the phrase has since mutated into a slogan for white supremacists and other hate groups, according to a report published on Tuesday by the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, an organization that tracks the spread of racism.

Thousands of posts using the slogan “white boy summer” have appeared on the Telegram app alone this year. It’s been used by far-right groups to recruit new followers, organize protests and encourage violence, especially against immigrants and L.G.B.T.Q. people, the report said.

For many of those who use it now, the phrase represents an unapologetic embrace of white heterosexual masculinity, often at the expense of women and people of color.

Increasingly, the meme has moved from the fringes of the internet into the political mainstream in the United States and elsewhere around the world, one of the group’s founders, Wendy Via, said.

Jack Posobiec, a podcaster whom the Southern Poverty Law Center has linked to white supremacists, waved a banner with the words “white boy summer” on it at a gathering for Turning Point USA, a conservative group, in Detroit last month. Former President Donald J. Trump was the conference’s keynote speaker, along with several members of Congress.

“It’s really about how quickly and how devastatingly something like this can go viral and the impact it has,” Ms. Via said of the phrase that Mr. Hanks coined. Extremists, she added, “are hurting people all over the world in the name of this thing.”

Mr. Hanks, 33, did not respond to numerous requests for comment through his social media accounts and the talent agency that represents him, but after this article appeared he posted a statement on Instagram condemning use of the phrase in any bigoted way.

“White boy summer was created to be fun, playful, and a celebration of fly white boys who love beautiful queens of every race,” he wrote. “Anything else that it has been twisted into to support any kind of hate or bigotry against any group of people is deplorable and I condemn it.”

Mr. Hanks started using the phrase in a series of posts on social media in 2021 about fashion and other advice for men. He seemed to anticipate that the meaning of the words required some explanation.

“Take it how you want it,” he said in a post on Instagram that March. “I’m not talking about, like, Trump, NASCAR-type white,” he went on, saying he meant people like himself and two other white R&B artists, Jon B. and Jack Harlow. “Let me know if you guys can vibe with that. And get ready, ‘cuz I am.”

His music video — produced under the name Chet Hanx — appeared the month after. It was a homage of a sort to the hit two years earlier by Megan Thee Stallion, “Hot Girl Summer,” featuring Nicki Minaj and Ty Dolla $ign.

It is replete with profanity, as well as sexist and racial slurs, but it also ends with an image of Mr. Hanks wearing a shirt with the words “stop hate” on it.

“White boy summer” is not the first artistic creation that white supremacists have hijacked and used online in hate speech.

Pepe the Frog, a comic book character created by Matt Furie, became so popular in racist, antisemitic and homophobic memes that the Anti-Defamation League classified it as a hate symbol in 2016. Mr. Furie killed off the character a year later, but it still circulates in ways he never intended.

Even before the meme, Mr. Hanks faced criticism for using — and defending the use of — a racial slur against Black people. He has also been accused of cultural appropriation after he started using, as an affectation, Jamaican patois in public appearances, including at the 2020 Golden Globe Awards, where Tom Hanks received the Cecil B. DeMille Award.

As a meme and a hashtag, “white boy summer” has with each passing summer been embraced by groups like the Proud Boys and “active clubs,” groups that blend racist ideologies with martial arts and other activities.

While more prevalent on fringe sites populated by extremist content, including Gab, Rumble and 4chan, the phrase also appears regularly on X, Instagram, Facebook and other major social media platforms, often with Nazi images. The phrase and its various hashtags appear to skirt policies that prohibit hate speech in part because it is often used euphemistically or ironically.

“While this trend/meme originated on the far right, it is definitely creeping into more ‘mainstream’ right-wing discourse,” said Todd Gutnick, a spokesman for the Anti-Defamation League, which documented the slogan’s spread early on.

The Global Project Against Hate and Extremism report noted that the meme was now being used by extremist groups in countries around the world.

A group in France created stickers with the phrase — in English — for members to distribute, while another in Finland held an annual festival last month using the phrase as its name. Writing about last year’s event, Bellingcat, a research organization, reported that attendees “watched far-right bands perform, participated in combat sports and mingled with other hate group members in hot tubs.”

“The far right is adept at bringing their hateful ideologies into the mainstream, especially through the use of social media,” the report said, “and the already-viral ‘white boy summer’ has proved to be the perfect segue from them to spread their bigotry to a wider audience.”

Mr. Hanks, who also previously performed as Chet Haze, has had much-publicized struggles with drugs and accusations of domestic abuse that have contributed to his rebellious persona as a performer. “He’s a grown man,” his older half brother, Colin, who is also an actor, said in a radio interview in 2016, when asked if he had ever intervened with advice. “He’s going to do what he wants to do.”

Tom Hanks does not appear to have commented publicly on his relationship with Chet Hanks, though the son recently posted a cross-generational exchange of text messages with him about the recent feud between the rappers Drake and Kendrick Lamar. In an interview with The New York Times in 2019, the father described his experience as a parent.

“Somewhere along the line, I figured out, the only thing really, I think, eventually a parent can do is say: ‘I love you, there’s nothing you can do wrong, you cannot hurt my feelings, I hope you will forgive me on occasion, and what do you need me to do?’” he said.

Despite the controversy over its spread, Mr. Hanks continues to embrace the meme. “I have consulted with the heavens, felt a westward breeze, and walked outside of a strip club and saw my shadow …,” he wrote on Instagram in May. “This will be a #WBS.” He ended the post with the emoji of a church.

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoMajor African Tribes taken away during the Atlantic Slave Trade🌍 #slavetrade #africanamericanhistory

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoCameroon 🇨🇲 World Cup History (1962-2022) #football #realmadrid #shorts

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Inventors: Mary Kenner 🩸

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoNo African pre-Columbus DNA? 🤯🤯 #history #mesoamerica #mexico #african