Sci-Tech

Investors Pour $27.1 Billion Into A.I. Start-Ups, Defying a Downturn

In May, CoreWeave, a provider of cloud computing services for A.I. companies, raised $1.1 billion, followed by $7.5 billion in debt, valuing it at $19 billion. Scale AI, a provider of data for A.I. companies, raised $1 billion, valuing it at $13.8 billion. And xAI, founded by Elon Musk, raised $6 billion, valuing it at $24 billion.

Such financing rounds have boosted the industry’s overall deal-making by dollar amount and number of deals, said Kyle Stanford, a research analyst at PitchBook.

“It’s not declining anymore,” he said. “The bottom has already fallen out.”

The activity has prompted some venture capital investors to change their message. Last year, Tom Loverro, an investor at IVP, predicted a “mass extinction event” for start-ups and encouraged them to cut costs. Last week, he declared that era over and christened this time the “Great Reawakening,” encouraging companies to “pour gas” on growth, particularly around artificial intelligence.

“The AI train is leaving the station & you need to be on it,” he wrote on X.

The start-up downturn began in early 2022 as many money-losing companies struggled to grow as quickly as they did in the pandemic. Rising interest rates also pushed investors to chase less risky investments. To make up for dwindling funding, start-ups slashed staff and scaled back their ambitions.

Then in late 2022, OpenAI, a San Francisco A.I. lab, kicked off a new boom with the release of its ChatGPT chatbot. Excitement around generative A.I. technology, which can produce text, images and videos, set off a frenzy of start-up creation and funding.

Sci-Tech

Samsung expects profits to soar with boost from AI

Samsung Electronics expects its profits for the three months to June 2024 to jump 15-fold compared to the same period last year.

An artificial intelligence (AI) boom has lifted the prices of advanced chips, driving up the firm’s forecast for the second quarter.

The South Korean tech giant is the world’s largest maker of memory chips, smartphones and televisions.

The announcement pushed Samsung shares up more than 2% during early trading hours in Seoul.

The firm also reported a more than 10-fold jump in its profits for the first three months of this year.

In this quarter, it said it is expecting its profit to rise to 10.4tn won ($7.54bn; £5.9bn), from 670bn won last year.

That surpasses analysts’ forecasts of 8.8tn won, according to LSEG SmartEstimate.

“Right now we are seeing skyrocketing demand for AI chips in data centers and smartphones,” said Marc Einstein, chief analyst at Tokyo-based research and advisory firm ITR Corporation.

Optimism about AI is one reason for the broader market rally over the last year, which pushed the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq in the United States to new records on Wednesday.

The market value of chip-making giant Nvidia surged past $3tn last month, briefly holding the top spot as the world’s most valuable company.

“The AI boom which massively boosted Nvidia is also boosting Samsung’s earnings and indeed those of the entire sector,” Mr Einstein added.

Samsung Electronics is the flagship unit of South Korean conglomerate Samsung Group.

Next week, the tech company faces a possible three-day strike, which is expected to start on Monday. A union of workers is demanding a more transparent system for bonuses and time off.

Sci-Tech

what next for ‘The Everything Company’?

By Tom Singleton, Technology reporter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThree decades on from the day it began, it is hard to get your head around the scale of Amazon.

Consider its vast warehouse in Dartford, on the outskirts of London. It has millions of stock items, with hundreds of thousands of them bought every day – and it takes two hours from the moment something is ordered, the company says, for it to be picked, packed and sent on its way.

Now, picture that scene and multiply it by 175. That’s the number of “fulfilment centres”, as Amazon likes to call them, that it has around the world.

Even if you think you can visualise that never-ending blur of parcels crisscrossing the globe, you need to remember something else: that’s just a fraction of what Amazon does.

It is also a major streamer and media company (Amazon Prime Video); a market leader in home camera systems (Ring) and smart speakers (Alexa) and tablets and e-readers (Kindle); it hosts and supports vast swathes of the internet (Amazon Web Services); and much more besides.

“For a long time it has been called ‘The Everything Store’, but I think, at this point, Amazon is sort of ‘The Everything Company’,” Bloomberg’s Amanda Mull tells me.

“It’s so large and so omnipresent and touches so many different parts of life, that after a while, people sort of take Amazon’s existence in all kinds of elements of daily life sort of as a given,” she says.

Or, as the company itself once joked, pretty much the only way you could get though a day without enriching Amazon in some way was by “living in a cave”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo the story of Amazon, since it was founded by Jeff Bezos in 1994, has been one of explosive growth, and continual reinvention.

There has been plenty of criticism along the way too, over “severe” working conditions and how much tax it pays.

But the main question as it enters its fourth decade appears to be: once you are The Everything Company, what do you do next?

Or as Sucharita Kodali, who analyses Amazon for research firm Forrester, puts it: “What the heck is left?”

“Once you’re at a half a trillion dollars in revenue, which they already are, how do you continue to grow at double digits year over year?”

One option is to try to tie the threads between existing businesses: the vast amounts of shopping data Amazon has for its Prime members might help it sell adverts on its streaming service, which – like its rivals – is increasingly turning to commercials for revenue.

But that only goes so far – what benefits can Kuiper, its satellite division, bring to Whole Foods, its supermarket chain?

To some extent, says Sucharita Kodali, the answer is to “keep taking swings” at new business ventures, and not worry if they fall flat.

Just this week Amazon killed a business robot line after only nine months – Ms Kodali says that it is just one of a “whole graveyard of bad ideas” the company tried and discarded in order to find the successful ones.

But, she says, Amazon may also have to focus on something else: the increasing attention of regulators, asking difficult questions like what does it do with our data, what environmental impact is it having, and is it simply too big?

All of these issues could prompt intervention “in the same way that we rolled back the monopolies that became behemoths in the early 20th century”, Ms Kodali says.

For Juozas Kaziukėnas, founder of e-commerce intelligence firm Marketplace Pulse, its size poses another problem: the places its Western customers live in simply can not take much more stuff.

“Our cities were not built for many more deliveries,” he tells the BBC.

That makes emerging economies like India, Mexico and Brazil important. But, Mr Kaziukėnas, suggests, there Amazon does not just need to enter the market but to some extent to make it.

“It’s crazy and maybe should not be the case – but that’s a conversation for another day,” he says.

Getty Images

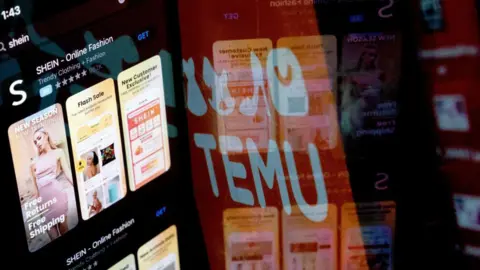

Getty ImagesAmanda Mull points to another priority for Amazon in the years ahead: staving off competition from Chinese rivals like Temu and Shein.

Amazon, she says, has “created the spending habits” of western consumers by acting as a trusted intermediary between them and Chinese manufacturers, and bolting on to that easy returns and lightening fast delivery.

But remove that last element of the deal and you can bring prices down, as the Chinese retailers have done.

“They have said ‘well, if you wait a week or 10 days for something that you’re just buying on a lark, we can give it to you for almost nothing,'” says Ms Mull – a proposition that is appealing to many people, especially during a cost of living crisis.

Juozas Kaziukėnas is not so sure – suggesting the new retailers will remain “niche”, and it will take something much more fundamental to challenge Amazon’s position.

“For as long as going shopping involves going to a search bar – Amazon has nailed that,” he says.

Thirty years ago a fledging company spotted emerging trends around internet use and realised how it could upend first retail, then much else besides.

Mr Kaziukėnas says for that to happen again will take a similar leap of imagination, perhaps around AI.

“The only threat to Amazon is something that doesn’t look like Amazon,” he says.

Sci-Tech

Ray Kurzweil Still Says He Will Merge With A.I.

Sitting near a window inside Boston’s Four Seasons Hotel, overlooking a duck pond in the city’s Public Garden, Ray Kurzweil held up a sheet of paper showing the steady growth in the amount of raw computer power that a dollar could buy over the last 85 years.

A neon-green line rose steadily across the page, climbing like fireworks in the night sky.

That diagonal line, he said, showed why humanity was just 20 years away from the Singularity, a long hypothesized moment when people will merge with artificial intelligence and augment themselves with millions of times more computational power than their biological brains now provide.

“If you create something that is thousands of times — or millions of times — more powerful than the brain, we can’t anticipate what it is going to do,” he said, wearing multicolored suspenders and a Mickey Mouse watch he bought at Disney World in the early 1980s.

Mr. Kurzweil, a renowned inventor and futurist who built a career on predictions that defy conventional wisdom, made the same claim in his 2005 book, “The Singularity Is Near.” After the arrival of A.I. technologies like ChatGPT and recent efforts to implant computer chips inside people’s heads, he believes the time is right to restate his claim. Last week, he published a sequel: “The Singularity Is Nearer.”

Now that Mr. Kurzweil is 76 years old and is moving a lot slower than he used to, his predictions carry an added edge. He has long said he plans to experience the Singularity, merge with A.I. and, in this way, live indefinitely. But if the Singularity arrives in 2045, as he claims it will, there is no guarantee he will be alive to see it.

“Even a healthy 20-year-old could die tomorrow,” he said.

But his prediction is not quite as outlandish as it seemed in 2005. The success of the chatbot ChatGPT and similar technologies has encouraged many prominent computer scientists, Silicon Valley executives and venture capitalists to make extravagant predictions about the future of A.I. and how it will alter the course of humanity.

Tech giants and other deep-pocketed investors are pumping billions into A.I. development, and the technologies are growing more powerful every few months.

Many skeptics warn that extravagant predictions about artificial intelligence may crumble as the industry struggles with the limits of the raw materials needed to build A.I., including electrical power, digital data, mathematics and computing capacity. Techno-optimism can also feel myopic — and entitled — in the face of the world’s many problems.

“When people say that A.I. will solve every problem, they are not actually looking at what the causes of those problems are,” said Shazeda Ahmed, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, who explores claims about the future of A.I.

The big leap, of course, is imagining how human consciousness would merge with a machine, and people like Mr. Kurzweil struggle to explain how exactly this would happen.

Born in New York City, Mr. Kurzweil began programming computers as a teenager, when computers were room-size machines. In 1965, as a 17-year-old, he appeared on the CBS television show “I’ve Got a Secret,” performing a piano piece composed by a computer that he designed.

While still a student at Martin Van Buren High School in Queens, he exchanged letters with Marvin Minsky, one of the computer scientists who founded the field of artificial intelligence at a conference in the mid-1950s. He soon enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to study under Dr. Minsky, who had become the face of this new academic pursuit — a mix of computer science, neuroscience, psychology and an almost religious belief that thinking machines were possible.

When the term artificial intelligence was first presented to the public during a 1956 conference at Dartmouth College, Dr. Minsky and the other computer scientists gathered there did not think it would take long to build machines that could match the power of the human brain. Some argued that a computer would beat the world chess champion and discover its own mathematical theorem within a decade.

They were a bit too optimistic. A computer would not beat the world chess champion until the late 1990s. And the world is still waiting for a machine to discover its own mathematical theorem.

After Mr. Kurzweil built a series of companies that developed everything from speech recognition technologies to music synthesizers, President Bill Clinton awarded him the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, the country’s highest honor for achievement in tech innovation. His profile continued to rise as he wrote a series of books that predicted the future.

Around the turn of the century, Mr. Kurzweil predicted that A.I. would match human intelligence before the end of the 2020s and that the Singularity would follow 15 years later. He repeated these predictions when the world’s leading A.I. researchers gathered in Boston in 2006 to celebrate the field’s 50th anniversary.

“There were polite snickers,” said Subbarao Kambhampati, an A.I. researcher and Arizona State University professor.

A.I. began to rapidly improve in the early 2010s as a group of researchers at the University of Toronto explored a technology called a neural network. This mathematical system could learn skills by analyzing vast amounts of data. By analyzing thousands of cat photos, it could learn to identify a cat.

It was an old idea dismissed by the likes of Dr. Minsky decades before. But it started to work in eye-opening ways, thanks to the enormous amounts of data the world had uploaded onto the internet — and the arrival of the raw computing power needed to analyze all that data.

The result, in 2022, was ChatGPT. It had been driven by that exponential growth in computing power.

Geoffrey Hinton, the University of Toronto professor who helped develop neural network technology and may be more responsible for its success than any other researcher, once dismissed Mr. Kurzweil’s prediction that machines would exceed human intelligence before the end of this decade. Now, he believes it was insightful.

“His prediction no longer looks so silly. Things are happening much faster than I expected,” said Dr. Hinton, who until recently worked at Google, where Mr. Kurzweil has led a research group since 2012.

Dr. Hinton is among the A.I. researchers who believe that the technologies driving chatbots like ChatGPT could become dangerous — perhaps even destroy humanity. But Mr. Kurzweil is more optimistic.

He has long predicted that advances in A.I. and nanotechnology, which could alter the microscopic mechanisms that control the way our bodies behave and the diseases that afflict them, will push back against the inevitability of death. Soon, he said, these technologies will extend lives at a faster rate than people age, eventually reaching an “escape velocity” that allows people to extend their lives indefinitely.

“By the early 2030s, we won’t die because of aging,” he said.

If he can reach this moment, Mr. Kurzweil explained, he can probably reach the Singularity.

But the trends that anchor Mr. Kurzweil’s predictions — simple line graphs showing the growth of computer power and other technologies over long periods of time — do not always keep going the way people expect them to, said Sayash Kapoor, a Princeton University researcher and co-author of the influential online newsletter “A.I. Snake Oil” and a book of the same name.

When a New York Times reporter asked Mr. Kurzweil if he was predicting immortality for himself back in 2013, he replied: “The problem is I can’t get on the phone with you in the future and say, ‘Well, I’ve done it, I have lived forever,’ because it’s never forever.” In other words, he could never be proved right.

But he could be proved wrong. Sitting near the window in Boston, Mr. Kurzweil acknowledged that death comes in many forms. And he knows that his margin of error is shrinking.

He recalled a conversation with his aunt, a psychotherapist, when she was 98 years old. He explained his theory of life longevity escape velocity — that people will eventually reach a point where they can live indefinitely. She replied: “Can you please hurry up with that?” Two weeks later, she died.

Though Dr. Hinton is impressed with Mr. Kurzweil’s prediction that machines will become smarter than humans by the end of the decade, he is less taken with the idea that the inventor and futurist will live forever.

“I think a world run by 200-year-old white men would be an appalling place,” Dr. Hinton said.

Audio produced by Patricia Sulbarán.

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoMajor African Tribes taken away during the Atlantic Slave Trade🌍 #slavetrade #africanamericanhistory

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoCameroon 🇨🇲 World Cup History (1962-2022) #football #realmadrid #shorts

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Inventors: Mary Kenner 🩸

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoNo African pre-Columbus DNA? 🤯🤯 #history #mesoamerica #mexico #african