Sci-Tech

Ampla, a Lender to Consumer Brands, Faces Financial Struggles

A popular lender backed by venture capital firms is struggling financially, sending shock waves through the small clothing and home furnishing companies that count on its financing.

The lender, Ampla, spent years courting small direct-to-consumer brands with low rates and a pitch that it understood their needs. In recent weeks, its top executives have been searching for a buyer, two people familiar with the firm’s finances said. Last week, Ampla, which is based in New York, said it would lay off half its 62 workers.

Ampla has also tightened or frozen clients’ lines of credit and told many customers to find other lenders, leaving them in the lurch, according to half a dozen former and current clients. The lender has served online businesses that emerged in the past decade to sell wares like silk knit sweaters, gluten-free cookies and 3-D printers for toys often directly to online shoppers, relying heavily on social media sites for marketing and buzz.

Its troubles appear to be part of a broader reckoning for direct-to-consumer businesses, some of which are no longer growing as rapidly as they once were or are struggling financially. Investors that were eager to back such firms are now being much more cautious.

Ampla, which was founded in 2019, has whittled the number of its borrowers down to around 100 to 150, one of the people familiar with its finances said. Some of those clients say they haven’t found anyone willing to lend to them at rates as low as Ampla’s. Many investors and banks became more wary of working with smaller and relatively untested businesses over the last two years as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates.

Ampla has been under pressure from its own lenders, including one that has stepped in to examine Ampla’s loan book after the firm breached a condition of its borrowing, the two people said.

The troubles began after Ampla unsuccessfully tried to raise more capital late last year and this year, the two people said. The company needed the money to stay in compliance with conditions imposed by its lenders, such as having a certain amount of cash on hand, as well as to fund its business, the people said.

Ampla has previously said its lenders included Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Waterfall Asset Management. Its investors include the venture capital firms Forerunner Ventures and VMG Partners.

Anthony Santomo, Ampla’s chief executive, and his co-founders, Jim Cummings and Jie Zhou, did not respond to requests for comment. VMG and Forerunner declined to comment.

The Information and Nosh earlier reported on Ampla’s financial troubles and its attempts to find a buyer.

Ampla has catered to firms with around $5 million to $50 million in annual revenue, according to one of the people familiar with its finances. Some of those direct-to-consumer brands weren’t big or established enough to borrow from a bank or another traditional lender.

“Ampla fills the gap in the market,” Forerunner Ventures said in a 2021 blog post.

Ampla customers say that the firm offered them loans at favorable interest rates and that the money allowed them to buy inventory and run marketing campaigns. On its website, the firm posted testimonials from current and former clients that described how Ampla loans allowed them to increase sales or secure distribution through large retailers.

Ben Perkins, founder of &Collar, a men’s dress shirt company, became an Ampla client in April 2022. The firm offered him an annualized interest rate of 17 to 19 percent, nearly half what other lenders required.

During key selling periods like Father’s Day and Black Friday, Ampla would increase his company’s credit line, enabling Mr. Perkins to stock more shirts. At one point, the credit line increased to $3 million, from $1.4 million.

But at the end of last month when Mr. Perkins got on a quarterly call with his Ampla account representative, he was told that &Collar’s credit line had been frozen. The representative suggested that the company find another lender.

“It very much blindsided us,” Mr. Perkins said. “We were not expecting it.”

He has since reached out to about 30 lenders, with some success. Mr. Perkins said he was fortunate not to have suffered the kind of slowdown that other direct-to-consumer companies had. He credits Ampla for helping him double his company’s revenue, which he expects to be about $15 million this year.

But Mr. Perkins worries that other direct-to-consumer companies may struggle to find another lender like Ampla. “I think it’s one of the bigger moments in D.T.C.,” he said. “I think there’s going to be decent fallout.”

Ampla’s origins are closely tied to the rise of the direct-to-consumer business.

Mr. Santomo, Ampla’s chief executive, co-founded Ampla after having been an early employee at Attentive, a start-up that helps brands send personalized texts to potential shoppers. His time at Attentive gave him and his co-founders the idea to create Ampla because they “recognized the opportunity to lend working capital to brands that otherwise would not have access to the scale and cost of capital Ampla could offer,” the 2021 Forerunner blog post said.

Since its founding five years ago, Ampla has raised $51 million in equity and $783 million in debt financing, according to PitchBook, which tracks start-ups and venture capital.

Ampla has used equity capital to lend money to its customers soon after they ask for it, later borrowing an equivalent amount from its lenders. As funds grew tighter this year, Ampla took more time to disburse loans, one of the people familiar with its finances said.

The company publicly highlighted that many of its clients were led by people of color or women, who typically have less access to credit than white people and men. In 2021, Ampla said it had worked with more than 200 brands and planned to double its work force.

Firms that worked with Ampla said that the company moved fast and that its employees were sharp and friendly. It accepted collateral that other lenders would not. Many borrowers signed on because Ampla offered relatively low rates — and kept them at those levels even as the Fed raised its benchmark rate.

Ampla made loans that one of the people familiar with its finances said appeared not to meet the standards the company had set for itself. Some of those customers ended up not abiding by the terms or fell behind on payments, the person said.

But as the Fed kept its benchmark rate high for months, Ampla’s costs became onerous. It had to start raising the interest rates of the loans it made, undercutting its appeal to smaller brands, the person said.

In at least one case, a customer defaulted on an Ampla loan worth several million dollars. Last week, Ampla sued the customer, Burke Decor, for breach of contract in federal court in Ohio, saying the furniture and home-goods brand owed Ampla $6.4 million, plus interest. Ampla said Burke Decor had misrepresented its finances when seeking a loan. Erin Burke, founder of Burke Decor, did not reply to a request for comment.

Ampla had secured big loans of its own as recently as a few months ago. In September, it said it had raised a $258 million credit warehouse — an arrangement to borrow money — with Goldman Sachs and Atalaya Capital Management. And in December, Ampla said it had closed on a similar $275 million arrangement with Citigroup and funds managed by Waterfall Asset Management.

Goldman Sachs, Atalaya, Citigroup and Waterfall Asset Management declined to comment.

One of the people familiar with Ampla’s finances said Atalaya was the only one of those lenders still extending credit to Ampla.

Some entrepreneurs in the direct-to-consumer category say the fallout from Ampla has shaken their confidence in the credit market. Many firms have refinanced with lenders like Dwight Funding, Parker, Ramp and Settle, according to former Ampla clients.

Alek Koenig, chief executive of Settle, which also started in 2019 and lends to smaller consumer goods brands, said that in the past four weeks his firm had been fielding requests from brands that previously used Ampla. A Google search for Ampla now often results in a sponsored ad that reads, “Looking to Switch From Ampla?”

Erin Griffith contributed reporting.

Sci-Tech

India’s X alternative to shut down services

Millions of social media users in India are stranded after homegrown microblogging platform Koo, which had branded itself as an alternative to X, announced it was shutting services.

The platform’s founders said a shortage of funding along with high costs for technology had led to the decision.

Launched in 2020, Koo offered messaging in more than 10 Indian languages.

It gained prominence in 2021 after several ministers endorsed it amid a row between the Indian government and X, which was then known as Twitter.

The spat began after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government asked the US-based platform to block a list of accounts it claimed were spreading fake news. The list included journalists, news organisations and opposition politicians.

X complied initially but then restored the accounts, citing “insufficient justification”.

The face-off continued as the government threatened legal action against the company’s employees in India.

Amid the row, a flurry of supporters, cabinet ministers and officials from Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) migrated to Koo overnight. Many of them shared hashtags calling for X to be banned in India.

By the end of 2021, the app had touched 20 million downloads in the country.

However, the platform has struggled to get funding in the last few years.

On Wednesday, founders Aprameya Radhakrishna and Mayank Bidawatka said that Koo was “just months away” from beating X in India in 2022, but a “prolonged funder winter” had forced them to tone down their ambitions.

“We explored partnerships with multiple larger internet companies, conglomerates and media houses but these talks didn’t yield the outcome we wanted,” they wrote on LinkedIn.

“Most of them didn’t want to deal with user-generated content and the wild nature of a social media company. A couple of them changed priority almost close to signing.”

In February, Indian news websites had reported that Koo was in talks to be acquired by news aggregator Dailyhunt. But the talks did not succeed.

In April 2023, Koo fired 30% of its 260-member workforce as the company faced severe losses and a lack of funding.

The founders said they would have liked to keep the app running – but the cost of technology services for that was high and so, they “had to take this tough decision”.

Sci-Tech

Would having an AI boss be better than your current human one?

By MaryLou Costa, Business reporter

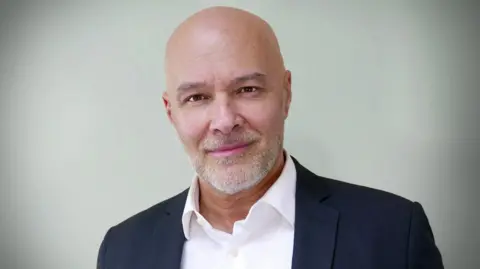

Hannu Rauma

Hannu RaumaWith the stress of managing 83 employees taking its toll, Hannu Rauma was feeling discouraged and frustrated.

“I was getting too bogged down in all these things that were going wrong amongst the teams, and feeling this disappointment,” says Mr Rauma, who is based in Vancouver, Canada.

He is a senior manager at a company called Student Marketing Agency, which employs university students to provide marketing support for small businesses.

“When I was bringing new clients on board, half of my mind would be saying, ‘we’re going to screw up’, and it would dampen my enthusiasm.”

But Mr Rauma says that all changed from last November, when the firm began using an autonomous AI manager developed by US-based company Inspira.

The AI manager helps the agency’s employees, who work flexible hours remotely, to set their schedules and plan their workloads in advance.

It checks their timekeeping, sends them deadline reminders and regular check-in messages, and records the time spent on different clients, so the latter can be billed accurately. The AI also makes suggestions to improve the wording of written text, is available to answer work-related questions, and automatically updates everyone’s work progress in a central portal.

Mr Rauma says that the shift towards an AI manager has not only reduced his stress levels, but has enabled his employees to work faster and be more productive. “I’m able to focus on the growth of the company and all the positive things. It’s added years to my life, I’m sure,” he says.

Mr Rauma adds that his relationships with his employees have also improved drastically. “Before, it felt a lot like a father-child situation. Now, we’re more on an equal footing. Before, it was only about solving problems. But now we’re able to have more light-hearted discussions.”

But not everyone at Student Marketing Agency is using the AI manager yet. Mr Rauma and 26 of his 83 employees were actually part of a study run by Inspira and academics from Columbia University, Arizona State University, and the University of Wisconsin to compare the performance of the AI manager with its human counterparts.

Participants were divided into three groups: one coached by a human manager, another by the AI manager, and the last group by both AI and human manager.

The AI manager achieved a 44% success rate in getting employees to pre-plan their workdays in advance, and was able to motivate the employees to log in on time 42% of the time. These figures were comparable to the human manager, who achieved scores of 45% and 44% for those two areas.

Yet when the AI manager worked in partnership with a human manager, together they achieved a 72% success rate in getting employees to pre-plan their workdays, and managed to achieve 46% on-time success.

Despite the study being statistically small, and concentrated on a specific type of worker and field, its results point to interesting implications for companies introducing AI tools.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile businesses like UPS, Klarna, Dell and others have announced significant job cuts this year, with the intention of replacing many roles with AI, Prof Paul Thurman, from Columbia University in New York, argues that swapping management roles completely for AI would be a mistake.

“The middle management layer is the most critical layer in any organisation,” says the professor of management. “They’re the layer that, if it starts turning over, you’re in for a wild ride. Your people don’t see continuity, they don’t get mentoring and coaching… all the human things that human managers are better at than AI and should be focusing on.”

AI, Prof Thurman adds, can liberate managers from endless reminding and checking in, to focus on more innovative ways of working. For example, managers can cherry pick project teams based on individual skillsets, oversee the brief, then hand over to their AI to manage minutiae like deadlines.

AI can also identify who in the team is falling behind and may need to be managed more closely by a human, and by the same token, hone in on star performers who require extra recognition.

But companies should steer away from AI managers becoming a surveillance tool, he says.

“You don’t want to get to a point where you are noting that, not only do people not clock in on time, but they take too much time at lunch, and they’re not eating enough salad. You don’t want to go that far,” says Prof Thurman. “You want to find the right way to encourage the right behaviours.”

AI managers can also help people who have become “accidental managers” – people who excel in their roles and end up managing people as a result, despite management not being a natural skill for them, says Tina Rahman, founder of London-based HR consultancy, HR Habitat.

“We did a study which looked at the reasons people leave a job. Almost 100% of the respondents said it was because of bad management.

“Some of them said they didn’t like the way they’d been managed, and most of them also said it was because they didn’t know what was expected of them or if they were doing a good job,” says Ms Rahman.

“You’d assume that an AI manager would be built to give those correct instructions, to give complete transparency on the requirements, and the outcomes. People are likely to be more productive when they know what’s expected of them.”

But an over-reliance on AI management sets the tone that companies only care about output and not people, Ms Rahman warns.

“It’s going to be very hard for a business to tell their employees that they’re introducing this brand new AI system that’s going to completely manage them, then say, with the same face, that ‘we care about your experiences in the workplace,’” she says.

James Bore

James BoreYet perhaps the biggest concern about AI managers is not from a people perspective, but from a cybersecurity one, warns James Bore, managing director of cybersecurity consultancy, Bores, and speaker and author.

“If you have an AI manager, and you’ve given them all of the company’s processes, procedures, and intellectual property that is suddenly all in the software, it can be kidnapped by someone who wants to clone it, and it could also be held to ransom,” says Mr Bore.

“If you’ve come to rely on it, which companies will when they start replacing humans with AI, you’re kind of stuck, because you’ve got no resilience, no option to switch back to the humans, because you don’t have them anymore.”

Rather than companies becoming more efficient through an extensive use of AI, Mr Bore says there could be an unintended consequence beyond becoming dependent on systems that could fail.

“The more you automate, and the more you remove people from your business, yes, you’ll bring down costs. But you will also make your company more replaceable.”

Sci-Tech

Judge Backs Challenge to F.T.C.’s Noncompete Ban, at Least for Now

A federal judge on Wednesday backed an initial legal challenge to the Federal Trade Commission’s ban on noncompete agreements, which is scheduled to take effect in September.

Judge Ada Brown granted an injunction requested by several plaintiffs, saying the ban cannot be enforced against them pending a final ruling.

But while the ruling is preliminary, she said that the F.T.C. lacked “substantive rule-making authority” with respect to unfair methods of competition and that the plaintiffs were “likely to succeed on the merits” of their challenge.

Judge Brown, of U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, said she expected to issue a final decision by the end of August.

The commission “stands by our clear authority, supported by statute and precedent, to issue this rule,” said Douglas Farrar, an F.T.C. spokesman. He added that the agency would “keep fighting” noncompetes in an effort to promote worker mobility and economic growth.

In April, the tax firm Ryan L.L.C. sued to block the near-total ban on noncompetes, just hours after the F.T.C. voted 3 to 2 to adopt the rule. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce later joined the case as a plaintiff, as did the Business Roundtable and two Texas business groups.

Banning noncompete agreements, which prohibit workers from switching jobs within an industry, would increase workers’ earnings by at least $400 billion over the next decade, the F.T.C. estimates. The agreements affect roughly one in five American workers, or around 30 million people, according to the agency, whose purview includes antitrust and consumer protection issues.

“If you’re not working in the most productive place you could be working because of a noncompete, that’s a loss for the economy,” Aviv Nevo, director of the F.T.C.’s Bureau of Economics, said at a conference in April.

Business groups argue that the ban would limit their ability to protect trade secrets and confidential information. The Chamber of Commerce and other groups assert that the F.T.C. lacks constitutional and statutory authority to adopt its proposed rule, with Ryan L.L.C. calling it “arbitrary, capricious, and otherwise unlawful.” Another lawsuit seeking to block the rule is pending in federal court in Pennsylvania.

But the three Democrats on the five-member commission maintain that it can legally issue rules defining unfair methods of competition under the F.T.C. Act of 1914, the law that created the agency. Their position has garnered some bipartisan support, too: Representative Matt Gaetz, Republican of Florida, argued in a brief filed in the Texas case that the noncompete ban falls “squarely within” the rule-making authority granted to the commission by Congress.

The Supreme Court’s decision last week to limit the broad regulatory power of federal agencies could raise the agency’s legal hurdles.

Mark Goldstein, a labor and employment lawyer at Reed Smith in New York, said that while limited to only the plaintiffs at this stage, Judge Brown’s injunction was a strong indication that she would deem the F.T.C.’s rule invalid, preventing it from going into effect nationwide.

“The writing is on the wall there,” Mr. Goldstein said. “I have never seen a court issue a preliminary injunction and then, absent some extremely unusual circumstances, issue a final decision that wasn’t consistent with the preliminary injunction.”

As litigation over the noncompete rule drags on, some lawyers are already advising employers to start relying more heavily on different agreements to protect trade secrets and business interests.

In a blog post after the F.T.C. adopted its noncompete ban, the law firm Winston & Strawn suggested that employers adopt alternative measures, such as narrowly tailored nondisclosure agreements and requirements that employees repay the company for training costs if they leave before a set period — known as training repayment agreement provisions, or TRAPs.

“Focus on these additional protections has become greater,” said Kevin Goldstein, an antitrust partner at Winston & Strawn.

But even those agreements are under increasing scrutiny. The commission’s final rule encompasses “de facto noncompetes” — measures that, in effect, prevent a worker from switching jobs within an industry, even if they aren’t labeled noncompete clauses. And employers are eyeing the shifting landscape of state and federal restrictions on such covenants, including nondisclosure agreements, beyond the F.T.C.’s rule.

While the commission’s vote to ban noncompetes has garnered the most attention, moves from other federal agencies and state legislatures against agreements that restrict worker mobility are simultaneously on the rise.

“There’s been increased hostility toward these agreements in general, across the country,” said Christine Bestor Townsend, co-chair of the unfair competition and trade secrets practice group at Ogletree Deakins.

Last month, a National Labor Relations Board judge ruled for the first time that a noncompete clause is an unfair labor practice, as part of her decision in an unfair-termination case. The judge also broke new ground by barring a nonsolicitation clause, which restricts soliciting clients or employees of a former employer; she argued that both types of agreements could chill protected activity, including union organizing.

That ruling followed a memo last year from the labor board’s general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, that clarified her view that noncompete provisions in employment contracts violate the National Labor Relations Act, except in limited circumstances.

“It’s one thing to get a guidance memo from the general counsel, which is significant and important,” said Jonathan F. Harris, an associate professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles who studies contracts and employment law. “And it’s another thing to see the adjudication side of the N.L.R.B. agree with her.”

These kinds of restrictive covenants tend to scare workers away from labor organizing, Mr. Harris said, “because the consequences of being fired for organizing become that much greater if you can’t get another job afterwards.”

Other federal agencies have jumped in as well, eyeing a range of employment provisions that they argue unfairly constrain workers. It’s part of the whole-of-government approach by the Biden administration to what it considers anticompetitive restraints on worker mobility.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, for example, issued a report last summer on the dangers of provisions requiring workers to repay training costs if they leave a job before a certain time elapses.

It’s not just a federal push: State governments are also stepping in to promote worker mobility — a trend that was in motion before the F.T.C. voted to ban noncompetes in April, but one that has gained momentum since.

Last month, the Rhode Island legislature passed a bill to ban noncompetes, joining Minnesota, California, Oklahoma and North Dakota. Dozens more states have enacted partial restrictions.

“Minnesota didn’t turn into a gaping crater,” said Pat Garofalo, the director of state and local policy at the American Economic Liberties Project, a progressive think tank, referring to the state’s wide-reaching ban on noncompetes that went into effect last year. “Once a domino falls over, a bunch of other dominoes fall over after.”

State laws can also prove more resilient to challenges than federal rules.

“State legislatures obviously have a lot of interest in getting these rules on the books right now,” Mr. Garofalo said.

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Facts I had to Learn on My Own pt.6 📜

-

African History5 years ago

African History5 years agoA Closer Look: Afro-Mexicans 🇲🇽

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoMajor African Tribes taken away during the Atlantic Slave Trade🌍 #slavetrade #africanamericanhistory

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoCameroon 🇨🇲 World Cup History (1962-2022) #football #realmadrid #shorts

-

African History5 months ago

African History5 months agoBlack History Inventors: Mary Kenner 🩸

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoPROOF AFRICAN AMERICANS AIN'T FROM AFRICA DOCUMENTED EVIDENCE

-

African History1 year ago

African History1 year agoNo African pre-Columbus DNA? 🤯🤯 #history #mesoamerica #mexico #african